Transregional Threats Journal

Texas Series • Volume 1 • Issue 2

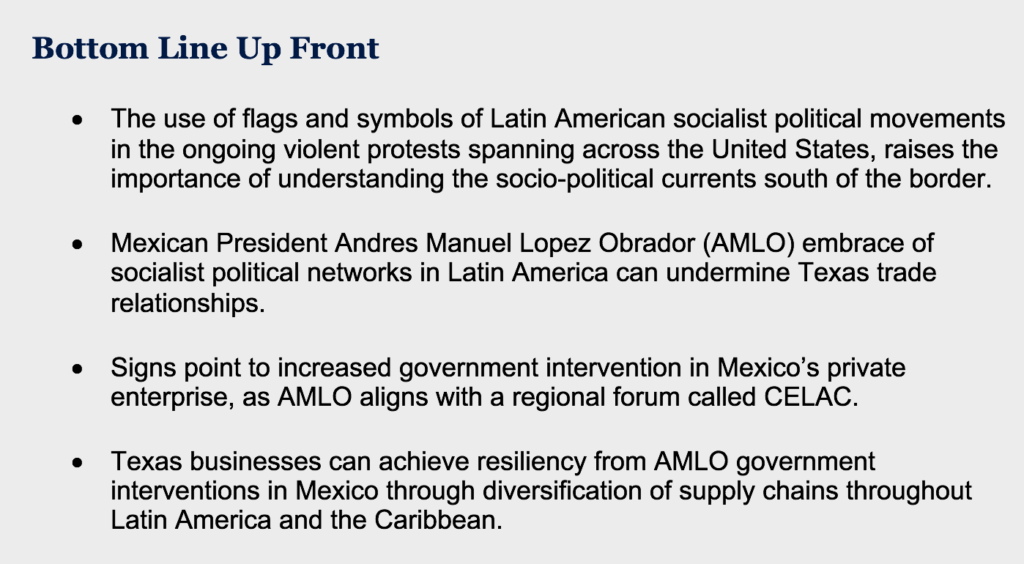

Why Texas should be wary of Mexico’s AMLO

For a region with 33 countries and more than 626 million people, Latin America and the Caribbean does not command the kind of attention it deserves in the United States. That is probably why a powerful political-criminal network has been able to organize without much attention.

The “Bolivarian Alliance,” once led by Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and now Nicolás Maduro, can be best understood as a transnational effort to achieve a 21st century socialism in the Americas. The alliance once consisted of eleven countries and three observers, to include Iran and Syria.[1] Its strength has since dwindled with the death of Chávez and the departure of member countries Bolivia, Ecuador, and most importantly with the 2018 election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

Today, however, the once-dominant alliance is reinvigorated with the ascent of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, or AMLO, to the presidency in Mexico in 2018. AMLO’s ideological affinities with the alliance will certainly influence Mexican policies. Anticipating the outcomes could position Texas businesses to better protect its relationships in Latin America in a post-pandemic world.

Texas relationship with Mexico

The criminal element that fuels so much of today’s Bolivarian Alliance presents enormous challenges for Texas’ security. For now, though, we are concerned with what sort of impact AMLO’s affinities for this socialist alliance may have on Texas’ relationships in the region.

There is no doubt of Mexico’s importance to America’s economic security. The United States and Mexico share a $614 billion trade relationship.[2] Mexico is also the number one trade partner of Texas. In fact, Texas’ exports to Mexico outpace its imports, which means Mexico holds a trade imbalance with the Lone Star State.[3] Trade deficits are not necessarily a bad thing, in terms of economics. But AMLO’s government intervention into the Mexican economy has the potential to diminish the source of that deficit—Texas private investment, 90 percent of which comes from small businesses.[4]

Six of the United States top ten trading ports with Mexico are in Texas. Those six ports of entry manage over half of the $614 billion trade between the United States and Mexico.[5] Keep in mind that Texas has 23 other official ports of entry.[6] It is not a stretch to say that Texas is the lynchpin for one of America’s most lucrative trade relationships.

The contents of the trade draw the conversation into the realm of national security as the top ten U.S. imports from Mexico have a primary use or dual use in critical infrastructure areas of cyber, transportation, and energy. Passenger vehicles, oil, computers and related parts arrive via Texas’ trade with Mexico.[7]

Therefore, a Mexican government that is receptive to anti-Americanism and opposed to free enterprise can cause serious long-term problems for Texas.

Mexico’s AMLO and the Bolivarian Network

Ideological extremism is not often associated with Latin America. Even the political zealotry of the Cold War in Latin America was largely an extension of foreign political influence. Few then give Latin American political movements the respect they deserve. That is probably why the Bolivarian Alliance has remained under-reported.

The alliance began as a brainchild of the late Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro and was formalized in December 2004 through a joint announcement by Venezuela and Cuba. Foreign policy expert Joel Hirst, who wrote a book on the Bolivarian Alliance, defines the organization as “a political and ideological alliance meant to form a common front in the establishment of an anti-American block in the region.”[8]

Chávez took his inspiration from 19th century hero Simón Bolívar who spearheaded the expulsion of Spanish forces and then became president of a short-lived experiment to create a single nation in Latin America, known as Gran Colombia. That project once held territory in the 17th century spanning roughly seven modern nations from Central to South America.[9]

The Bolivarian Alliance survives today more as an ideological support system and transnational criminal network led by Venezuela and Cuba. While its political power has weakened since the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013, the public sentiments that brought the alliance to power still resonate with many Latin American social movements and indigenous groups.[10] That ideological component remains committed to socialist and autocratic agendas for the express purpose of opposing the United States.

The alliance appears to have a sympathetic partner in Mexican President Lopez Obrador. The AMLO government has repeatedly sided with autocratic regimes, like Cuba and Russia, by rejecting international requests to shun Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro.[11] AMLO has “spurned” a regional and global consensus against the Maduro regime using the veneer of non-interference to justify its position, despite those close to the president having openly expressed support for the Venezuelan regime.[12]

Meanwhile, Mexican oil companies with little or no track record in the oil market have been found delivering oil to Venezuela, some through foreign ports, to avoid U.S. sanctions. It remains a mystery how previously unknown oil companies have been able to access such significant amounts of oil in Mexico.[13]

Mexican state oil giant Pemex continues to claim ownership over the majority of an offshore deposit in the Gulf of Mexico discovered and managed by a private consortium of investors, led by Talos Energy out of Houston. One report called the moves by the AMLO administration and state-run Pemex as a “potentially troubling sign for private sector investment in Mexico.”[14] It might be more than that.

Experts on the Bolivarian Alliance have noted the most troubling aspect of the alliance was Venezuela’s formal strategy to join member economies through government-controlled energy production and to use the regions collective energy sector as a weapon against the United States.[15] Chavez’s original plan may not be a reality today. But the intent remains.

Troubling economic ventures by the AMLO regime go beyond Venezuela. Argentina’s newest head of state President Alberto Fernandez used his first foreign visit as president-elect in November 2019 to meet with AMLO in Mexico. Fernandez called for a revival of the progressive political forum, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), an idea to which AMLO’s deputy foreign minister spoke positively.[16] CELAC was established in 2010 by then-President Hugo Chavez as a regional political bloc to counter the Organization of American States (OAS) and the United States. Mexico will lead CELAC in 2021. Maduro went on to praise both AMLO and Fernandez during a speech in Cuba as the new progressives of Latin America.[17]

During this trip to Mexico, then Argentine President-elect Fernandez also joined the inaugural meeting of the so-called Grupo Puebla, a recent conglomerate of left-leaning, regional political leaders, such as Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, Bolivia’s Evo Morales, and Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Dilma Rousseff.[18] The Grupo Puebla seems poised to pick up where the Bolivarian Alliance left off.

AMLO routinely downplays these relationships and redirects to non-interference as a reason for the administration’s neutrality on Venezuela. The public coyness makes it difficult to know how Mexico will approach free enterprise in the future. But in a stroke of historical irony, a story out of Argentina may help Texas readers contextualize, even forecast, AMLO’s murky intentions.

Argentina: Not Just Another History Lesson

The first administration of Argentine President Juan Perón (1946-1952) faced one of the most consequential deliberations of our times when the United Nations brought forward a vote on the partition plan for Palestine in 1947. The Perón administration chose to abstain in what many historians today incorrectly label as simple non-interference—something Perón trumpeted as reason for Argentina’s neutral position.

Looking back, Perón chose to abstain, at least partly, because he intended to counter western nations through cooperation with autocratic governments in the Arab World. Anything other than a “yes” vote benefited the Arab representatives who only wanted to kill the plan. Abstention supplied Perón the veneer of non-interference while guaranteeing support for the Arab plan.[19] History bears that out.

The Syrian government in 1950 named a street in Damascus after Perón for “sticking to the Arab side in the United Nations.”[20] Argentina’s delegate to the United Nations was such an avid Arab supporter that the Jewish community had already concluded Argentina was committed to the Arab side. Perón even deployed a reputed Arab emissary to Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Saudi Arabia two months before taking office to pursue political and economic cooperation with Arab nations. The evidence goes on.

He ultimately failed for many reasons, some unrelated to the Arab project. But for the purposes here, we see how non-interference can be a convenient political tool to distract from actual intentions, especially for those with socialist leanings who also have economic interests with United States. Positive responses from autocratic regimes only raise suspicions.

The AMLO administration shares some striking similarities with Perón and their actions deserve considerable scrutiny. Interestingly, the new Alberto Fernandez government of Argentina is considered Peronist, a term used for those who embrace the economic centralization and nationalist principles of Juan Perón. That Argentine President Fernandez first foreign visit was to Mexico should not be underestimated.

Supply Chain Solutions

The Bolivarian Alliance appears to be using broader political movements, such as CELAC and Grupo Puebla, to rebrand itself, while it continues to use the COVID-19 pandemic to push for reforms to expand state-control over local economies.[21]

The Latin American energy sector has always been a prime target for those reforms. One senior executive at one private international power company recently stated: “There’s a very strong ideological vision—they [AMLO government] want government control to use energy as a lever of development.”[22] This sentiment is causing concern throughout the private sector in Mexico. Diversification may be the way for Texas companies to build resiliency against government alliances hostile to free enterprise.

Scholar Merrill Matthews with Institute for Policy Innovation (IPI) made the observation that diversified international supply chains are less vulnerable to disruptions and a better response to America’s dependence on China for pharmaceuticals. He was referencing the instincts of Peter Navarro, economic advisor to President Trump, who wanted to headquarter “everything in the United States.”[23] His observations bring to mind Texas’ reliance on Mexico.

The COVID-19 environment has taught Texas that post-pandemic business interests in Mexico need diversified supply chains to improve their prospects for long-term sustainability. Diversifying business interests throughout Latin America could be an option against ALMO’s shift toward government centralization. That approach would maintain the geographic benefits of being in the region and increase flexibility in future decisions.

Now, Mexico is not to Texas what China is to America. But the AMLO administration’s affinity for those who oppose free enterprise and free societies portend a future that could threaten Texas small businesses – the backbone of Texas-Mexico trade.[24]

Notes

[1] At the height of its influence in 2013, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA) consisted of twelve member countries: Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, with Haiti, Suriname, Iran, and Syria as guest or observer members.

[2] Erin Douglas and James Osbourne, “Tariffs on Mexico could deal a blow to Texas economy,” Houston Chronicle, May 31, 2019.

[3] Julián Aguilar, “Experts say COVID-19 could hurt Texas trade and border economy,”

Texas Tribune, March 6, 2020; Mexico, “Top Trading Ports,” WorldCity, Inc. Last accessed on May 19, 2020 at https://www.ustradenumbers.com/country/mexico/; Laurie Joseph and Mitchell Schnurman, “Why Texas has so much riding on trade and Mexico,” Dallas Morning News, April 21, 2017.

[4] UN predicts recession in LatAm due to virus,” Yahoo, April 3, 2020; Juan Montes and David Luhnow, “Mexico’s Leader Has Answer for All His Needs: The Army,” Wall Street Journal, May 28, 2020; Texas Economic Development, “Trade and Export,” Office of the Texas Governor. Last accessed on May 29, 2020 at https://gov.texas.gov/business/page/trade-and-export.

[5] Aguilar, “Experts say COVID-19 could hurt Texas trade and border economy,”; Mexico, “Top Trading Ports,”; “Texas U.S. Ports of Entry,” Office of the Governor, Economic Development and Tourism; Joseph and Schnurman, “Why Texas has so much riding on trade and Mexico.”

[6] Texas Comptroller, “Economy: Texas Ports of Entry.” Last accessed May 29, 2020 at https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/economic-data/ports/

[7] Mexico, “Top Trading Ports,”

[8] Joel Hirst, The ALBA: Inside Venezuela’s Bolivarian Alliance (Miami: Interamerican Institute for Democracy, 2012) 94.

[9] The state of Gran Colombia existed from 1819 to 1831 and included territories of present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela, and parts of northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwestern Brazil.

[10] The Maduro regime has also strengthened the alliance by fusing the political objectives with criminal networks throughout Latin America. That will be discussed in future publications.

[11] Shannon K. O’Neil, “Mexico is Making the Wrong Bet on Venezuela,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 20, 2019.

[12] Jose Orozco, “Mexico Sidelined as EU, Uruguay Push Venezuela Vote,” Bloomberg, February 7, 2019; O’Neil, “Mexico is Making the Wrong Bet on Venezuela,”; Hector Gutiérrez, “En redes, secretaria general de Morena promueve a Maduro,” El Financiero, July 3, 2017.

[13] Emmanuel Alejandro Rondon, “Mexican Company Helps Venezuela’s Maduro to Avoid U.S. Sanctions,” Panam Post, April 15, 2020.

[14] David Alire Garcia, “Exclusive: Standoff with Pemex is slowing talks over developing oil find – Talos CEO,” Reuters, February 11, 2020.

[15] Hirst, The ALBA, 86.

[16] Frank Jack Daniel, “Latin American left rising? First stop Mexico for Argentina’s Fernandez,” Reuters, November 5, 2019.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Nicolás Misculin, “Argentina’s Fernandez joins leftist leaders for ‘Puebla Group’ summit,” Reuters, November 9, 2019.

[19] David Grantham, “Argentina, the Arab World, and the Partition of Palestine, 1946-1947” Journal of Global South Studies, Vol 36, No 1 (2019), 88-115.

[20] Ibid, 9.

[21] “Que busca el Grupo de Puebla ante la crisis por la pandemia del Covid-19,” Comerico, May 23, 2020.

[22] Jude Webber, “Investors See an Uncertain Future In Mexico,” Financial Times, May 24, 2020.

[23] Merrill Matthews, “Pandemic-induced protectionism endangers lives,” Hill, April 3, 2020.

[24] Texas Economic Development, “Trade and Export,” Office of the Texas Governor. Last accessed on May 29, 2020 at https://gov.texas.gov/business/page/trade-and-export.