LATIN AMERICA’S LEFT: A SURVEY

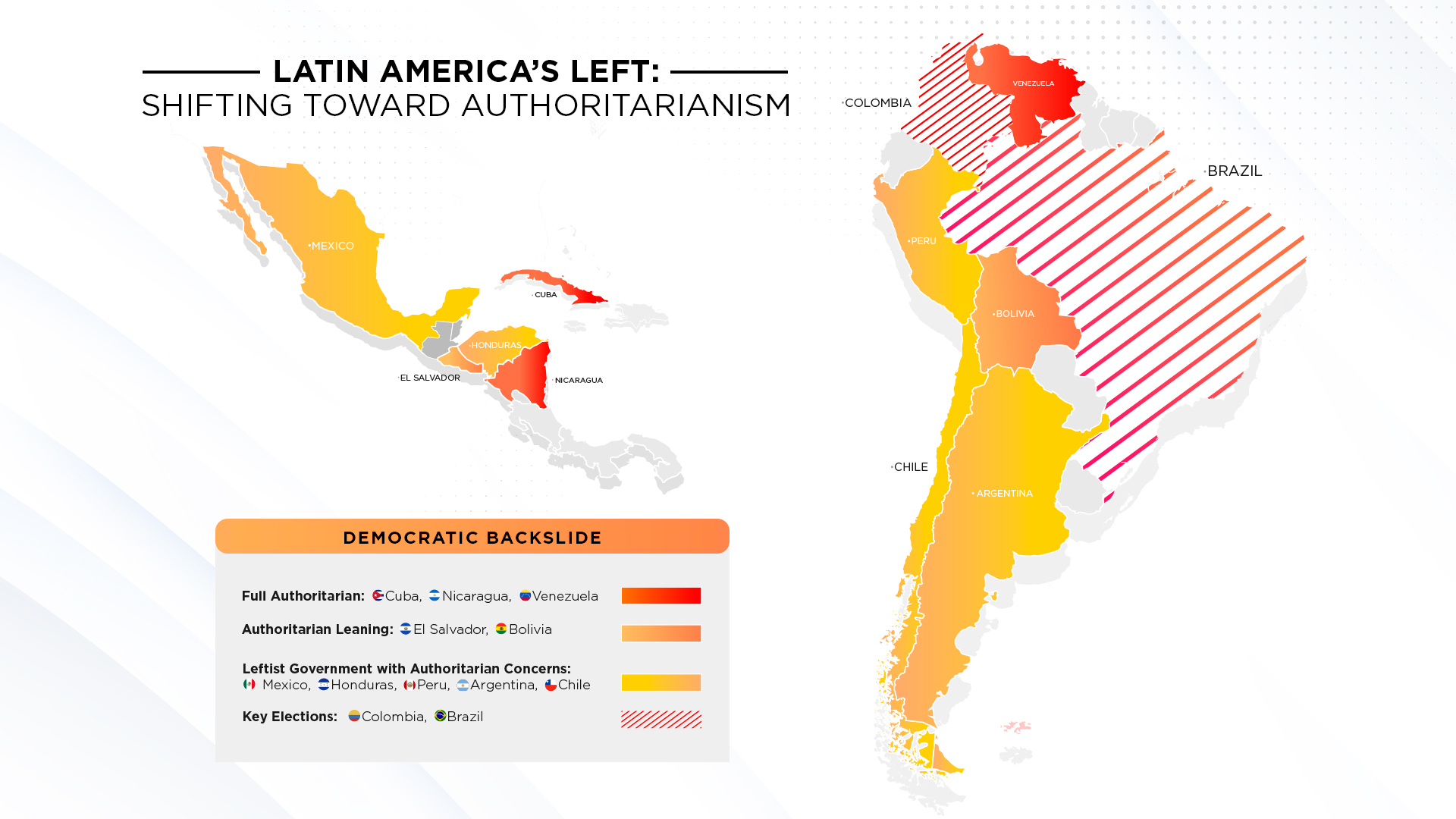

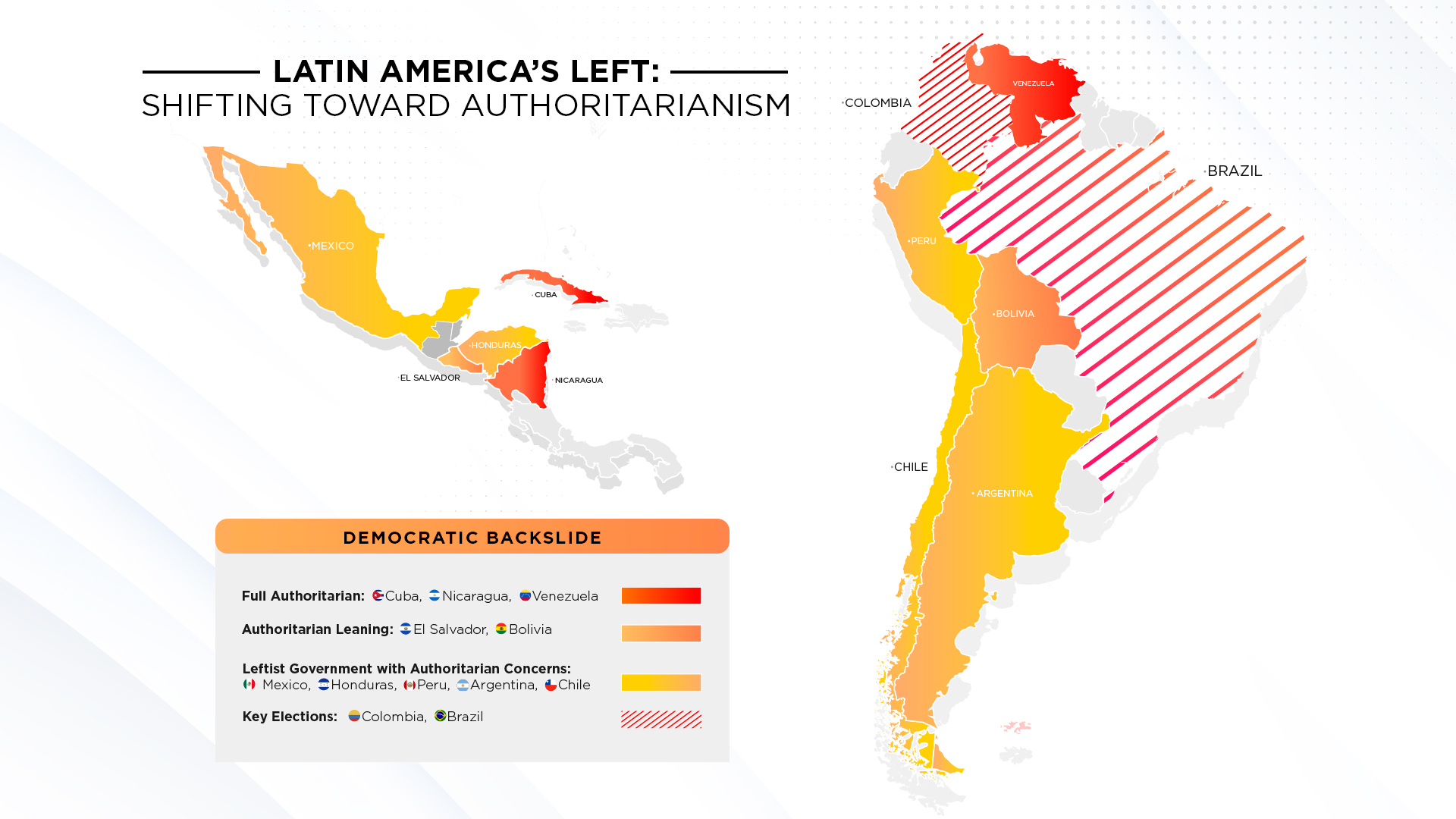

With the exception of the authoritarian regimes in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, the common element of the other left-oriented governments in Latin America, and those that may come to power in 2022, is the mixture within them of democratic actors versus autocrats whose policies would polarize society and radicalize its base.

This includes some with authoritarian tendencies who seek to deliberately hijack democratic institutions for malevolent ends.[10] With this context, it is useful to survey the current political landscape of the Latin American left and state specific concerns of some of the recent actions taken by the relatively new governments in each country.

This includes some with authoritarian tendencies who seek to deliberately hijack democratic institutions for malevolent ends.[10] With this context, it is useful to survey the current political landscape of the Latin American left and state specific concerns of some of the recent actions taken by the relatively new governments in each country.

Mexico

Mexico

In Mexico, political expression and competition by traditional parties such as the PRI, PAN and PRD continue to be viable. While President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) may be a popular president, he has sought to eliminate democratic obstacles to his policies.

For instance, an attempt to expedite approval of a new national security law in 2020 would impede security cooperation with the U.S. and likely expand criminal activity in the country.[11]

In addition, AMLO has pursued economic policies that would marginalize Mexico’s deeply rooted private sector,[12] including favoring statist approaches to the critical petroleum,[13] electricity,[14] and lithium[15] sectors, among others, risking an economic crisis and increased polarization.

In addition, AMLO has pursued economic policies that would marginalize Mexico’s deeply rooted private sector,[12] including favoring statist approaches to the critical petroleum,[13] electricity,[14] and lithium[15] sectors, among others, risking an economic crisis and increased polarization.

Other worrisome actions by AMLO and his Morena political party include their public dismissal of criminal charges against the former head of the Mexican Army Salvador Cienfuegos,[16] as well as AMLO’s personal visits to the mother of narcotrafficking kingpin “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera.[17]

Honduras

Honduras

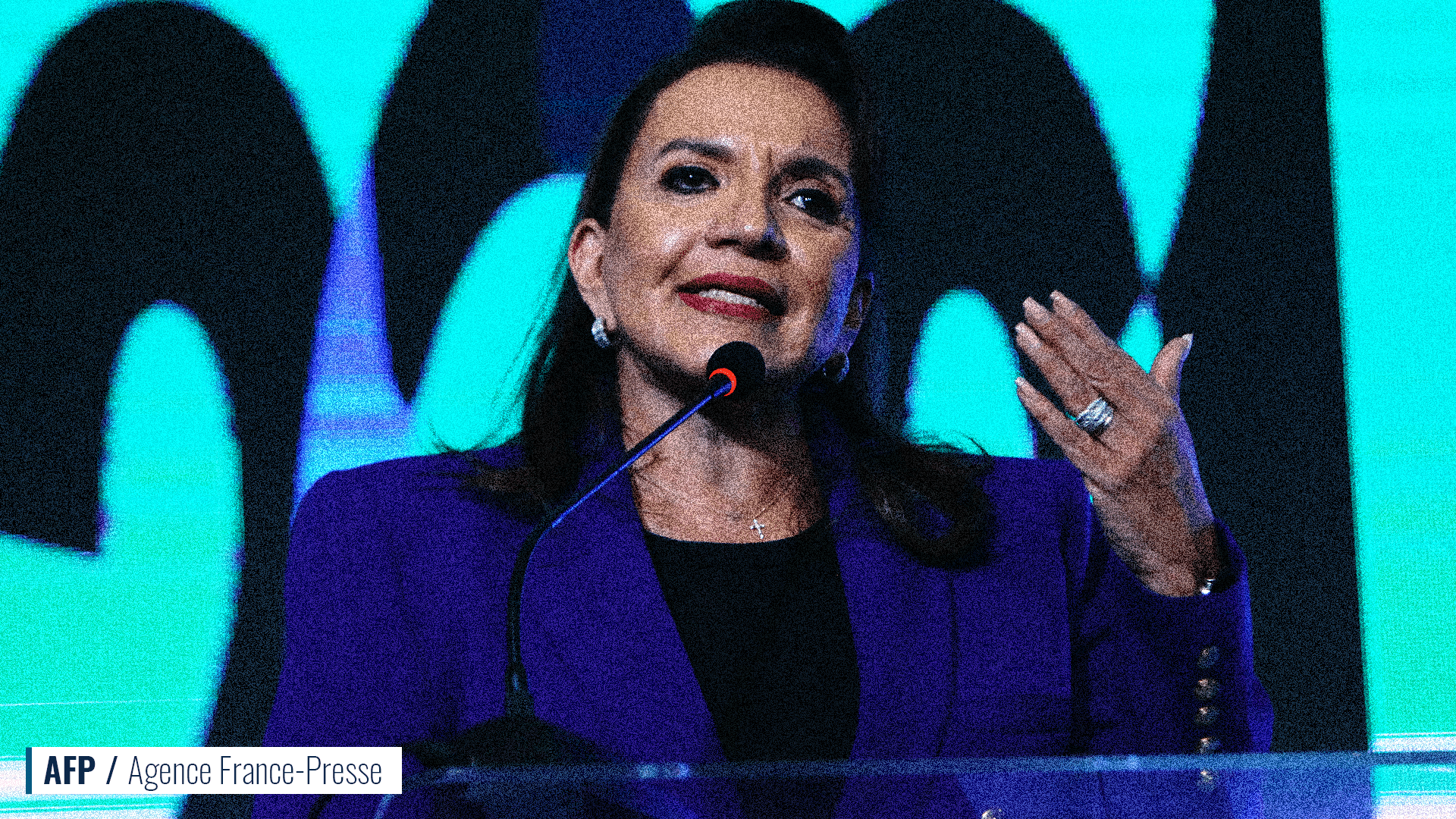

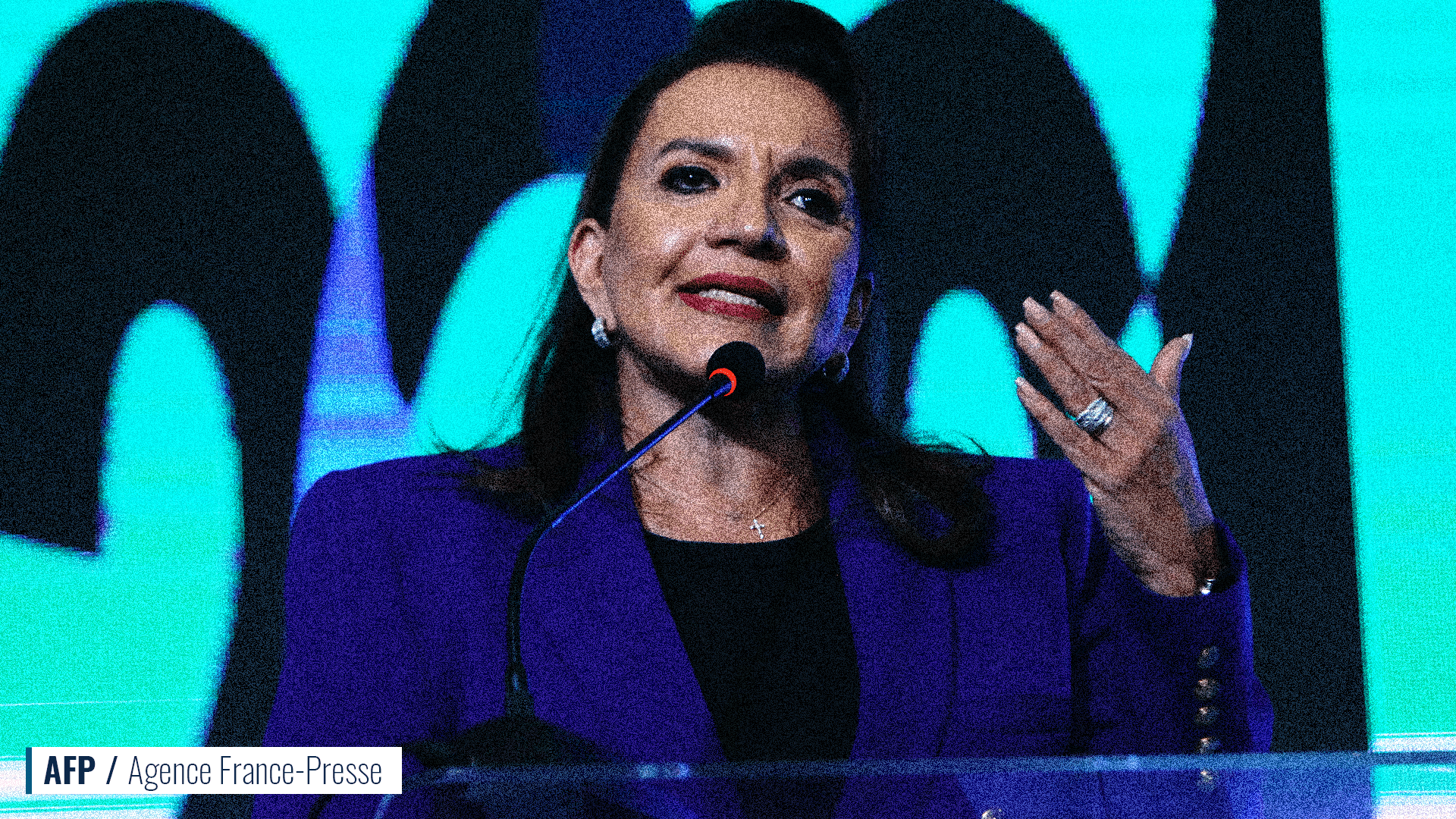

The new government of President Xiomara Castro appears to be in an internal struggle between democratically-oriented figures in her cabinet, such as Vice President Salvador Nasrallah, versus more radical actors, including her own husband and former President Manuel “Mel” Zelaya.[18]

It’s worth remembering that Mel Zelaya was accused of receiving illicit funding from Hugo Chavez in Venezuela back in 2010.[19] This internal struggle within the ruling party in Honduras surfaced in January 2022 when a Zelaya-led faction of President Castro’s political party, Libre, in conjunction with members of the National Party, sought to undercut Xiomara Castro’s selection for parliamentary speaker.[20]

It’s worth remembering that Mel Zelaya was accused of receiving illicit funding from Hugo Chavez in Venezuela back in 2010.[19] This internal struggle within the ruling party in Honduras surfaced in January 2022 when a Zelaya-led faction of President Castro’s political party, Libre, in conjunction with members of the National Party, sought to undercut Xiomara Castro’s selection for parliamentary speaker.[20]

Similarly, it is believed that some of these same radical elements within the new Castro government led the president to switch diplomatic recognition from the de jure interim government of Juan Guaido to the illegitimate regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela. It is noteworthy that Venezuela is the principal transit point of drugs and illicit funds flowing to and through Honduras, whose associated corrupting influences the Xiomara Castro government is theoretically committed to combat.[21]

Peru

Peru

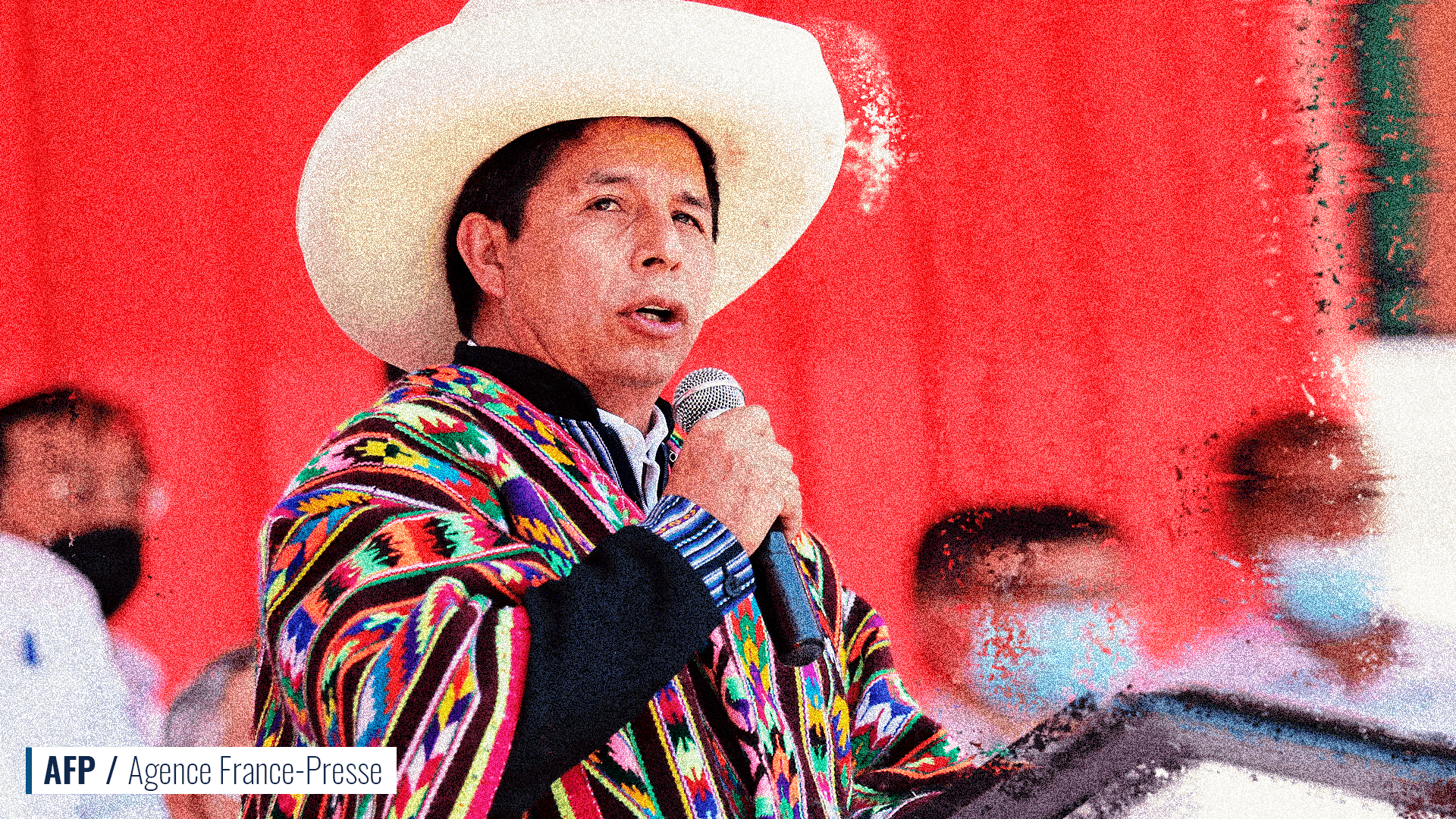

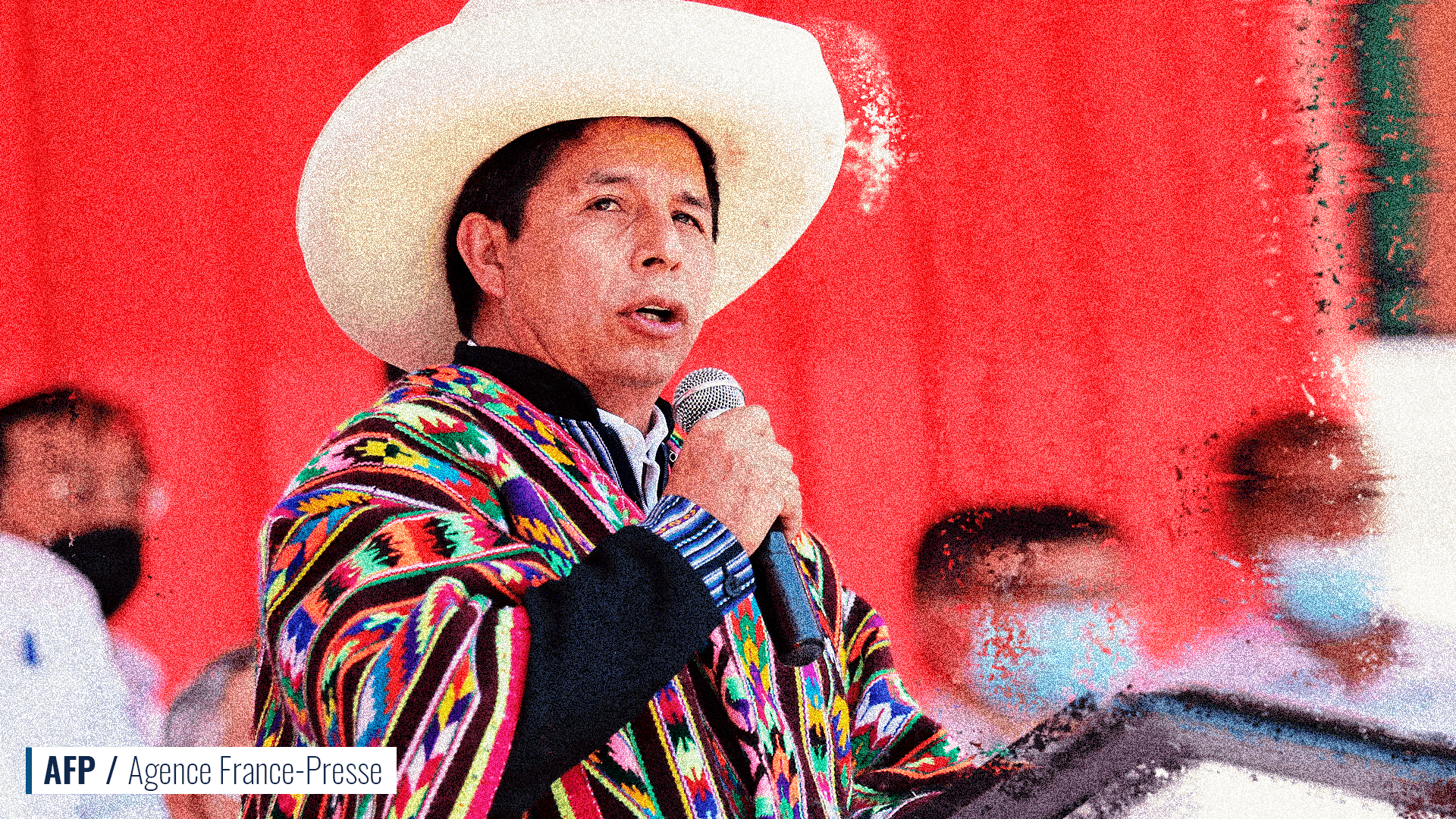

President Pedro Castillo, the politically inexperienced teacher from Cajamarca has arguably found himself in over his head with respect to the complex politics of Peru. To some degree, Castillo has tried to distance himself from Venezuela’s Chavista regime calling it “not the path to follow.”[22]

And has tried to maintain his own voice[23] against subversive influences within his political party, Peru Libre, such as Cuban-trained doctor Vladimir Ceron, pushing back against Ceron’s preferred cabinet picks.[24]

The result has been political paralysis with a consistent stream of cabinet reshuffling, replacing a minister on average every nine days within his first nine months in office.[25] President Castillo’s difficulties come on top of the crisis of corruption and governance that began in 2017 and saw three Presidents seated in a five-day period in November 2020.[26]

The present deepening of that crisis of governance theoretically opens a range of options from widespread political violence to a looming impeachment trial in the National Congress, which could result in an even more radical leftist authoritarian leader rising to power in Peru.

The present deepening of that crisis of governance theoretically opens a range of options from widespread political violence to a looming impeachment trial in the National Congress, which could result in an even more radical leftist authoritarian leader rising to power in Peru.

Argentina

Argentina

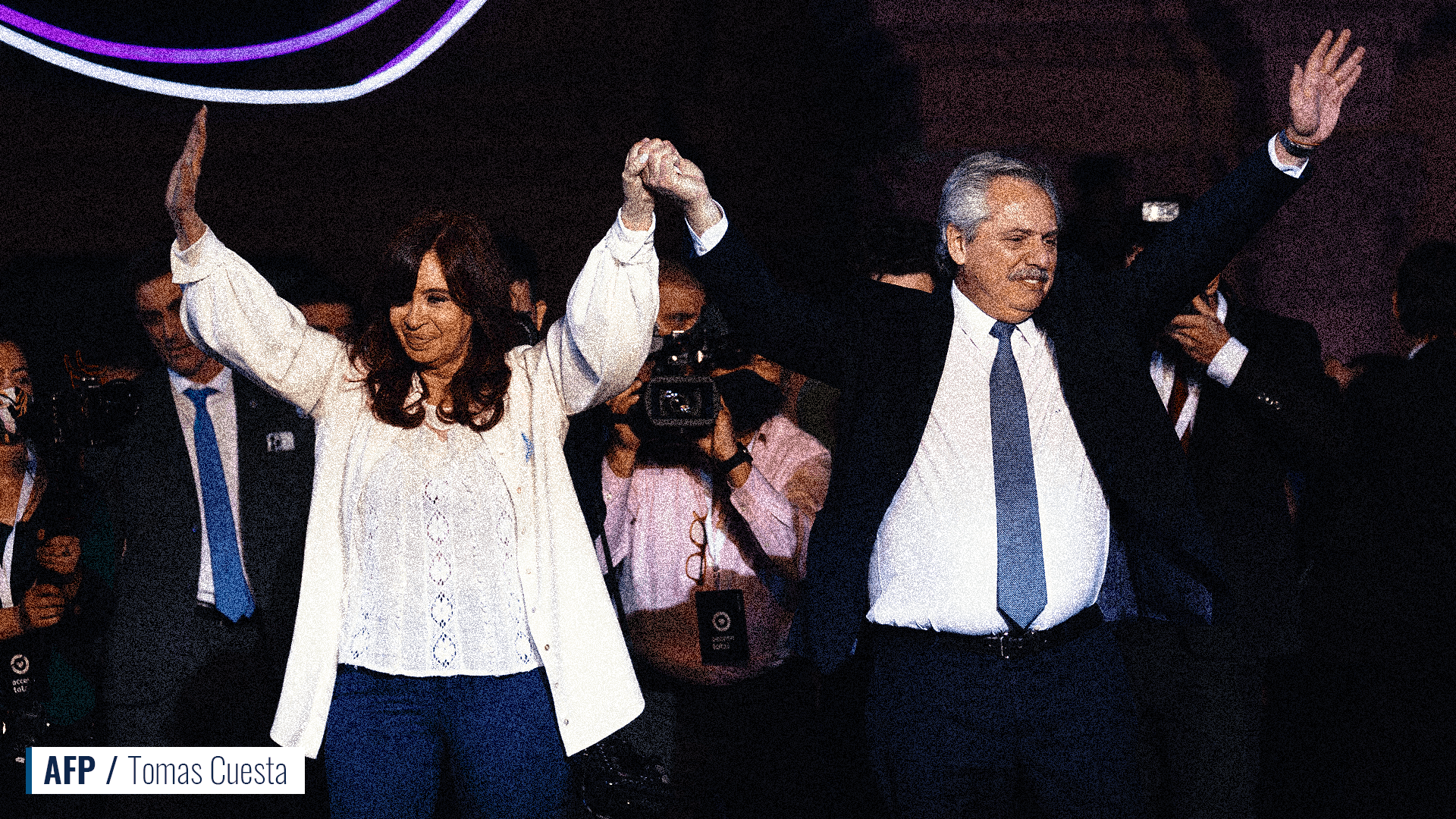

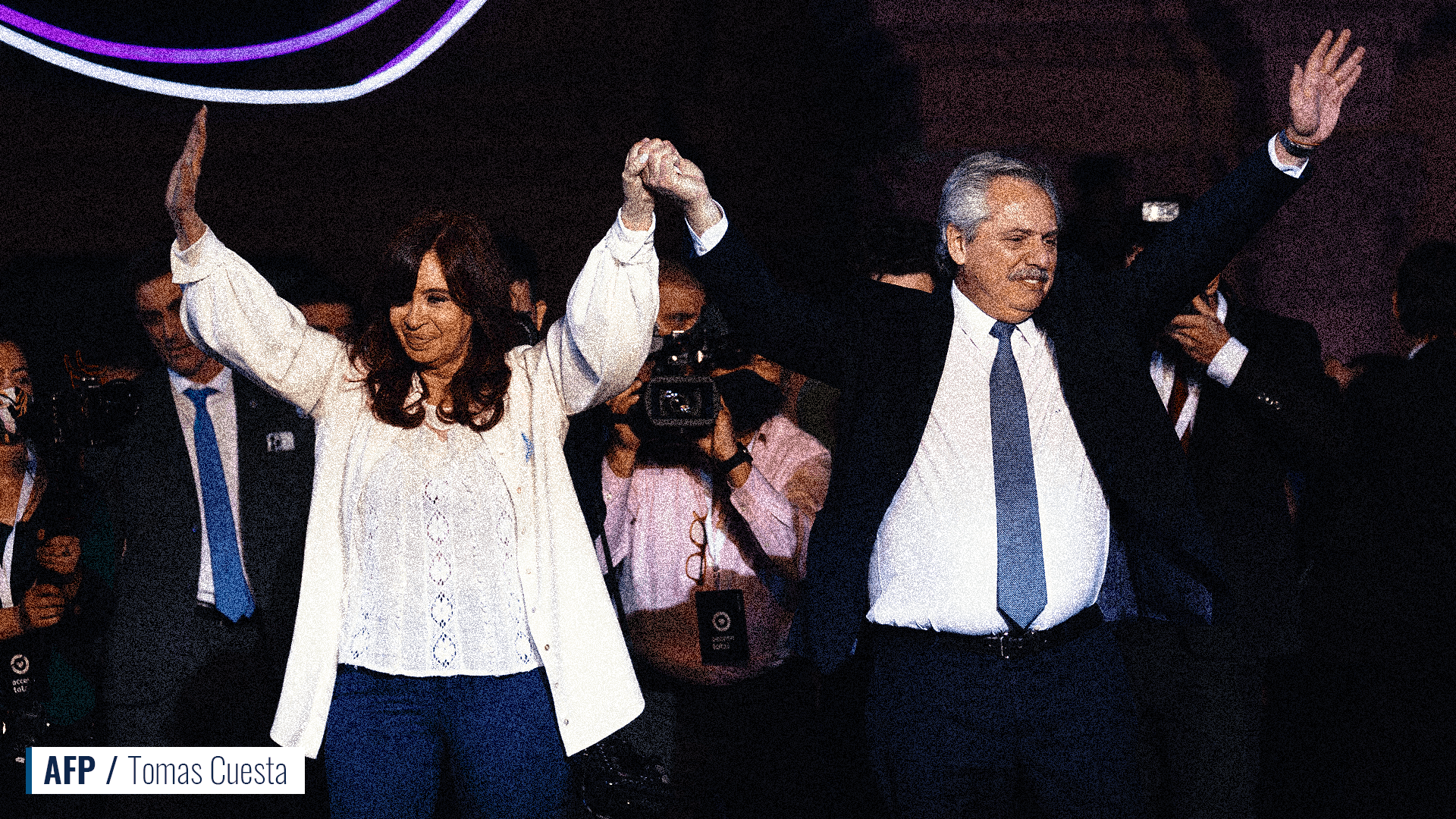

President Alberto Fernandez initially presented himself to voters as a moderate within Peronism by contrast to his predecessor and now Vice President Christina Fernández de Kirchner, but after a couple years in power there are indications that the VP is increasingly calling the shots.[27] Steadily increasing her influence within the government, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner allegedly pressured several changes to cabinet ministers in September 2021.[28]

Alberto Fernandez’ controversial public overture[29] to Russia’s Vladimir Putin during his state visit[30] to Moscow and Beijing[31] in February 2022 raised questions about the Argentine president’s judgement and moderation.

Moreover, attempts by some within Peronism in 2020 to replace judges investigating corruption cases involving their networks raised questions about Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the left in Argentina’s aims to consolidate power and undermine the independence of government institutions.[32]

Moreover, attempts by some within Peronism in 2020 to replace judges investigating corruption cases involving their networks raised questions about Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the left in Argentina’s aims to consolidate power and undermine the independence of government institutions.[32]

Chile

Chile

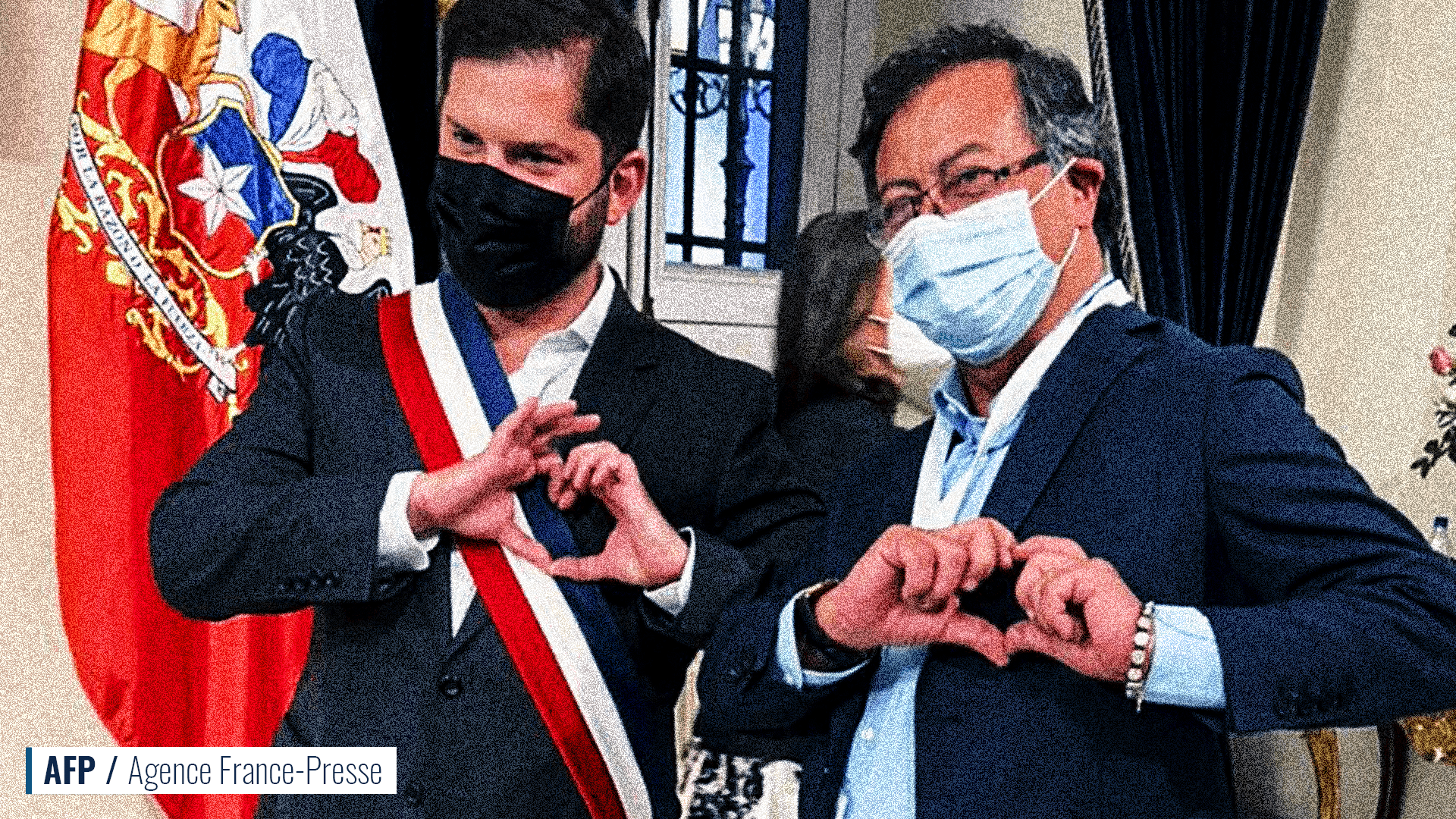

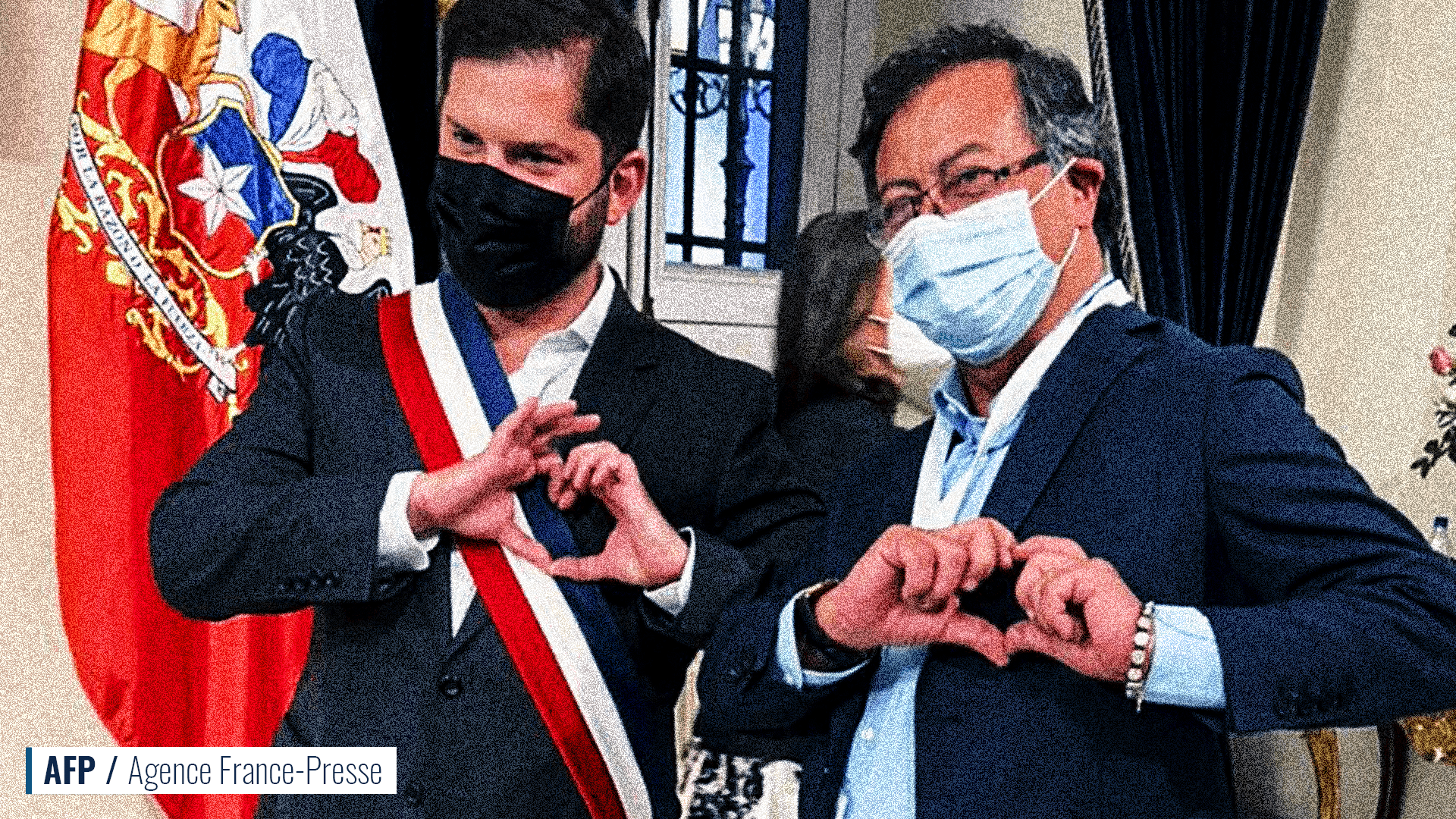

The most recent addition to Latin America’s left is the youthful Chilean President Gabriel Boric. The key partner within his Apruebo Dignidad coalition that helped achieve electoral success is the Chilean Communist Party and its influential leader Guillermo Tellier del Vale. Less than one month in office, Boric has appointed far left figures to key cabinet positions, although he has also reached out to moderates, and taken public positions against both Russia’s unprovoked invasion of the Ukraine and anti-democratic regimes in Latin America.

Although President Boric named respected Central Bank head Mario Marcel to be finance minister, for defense minister, he has named Maya Fernández Allende, whose grandfather was forced out of power in 1973 by the same Chilean military she is now leading.[33] Ms. Allende, herself, grew up in Cuba with her family.[34]

While the Chilean Congress, currently dominated by the right and center-left, can challenge potential harmful policies of the new Boric government, this may tempt the millennial leader to leverage leverage the ongoing process of changing the constitution to overcome that resistance.[35]

The Constitutional Convention has already demonstrated a radical posture even beyond President Boric’s governing coalition, with policy proposals such as abolishing all existing Chilean government structures and replacing them with a “plurinational assembly.”[36]

Dr. Evan Ellis is a research professor of Latin American Studies at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, with a focus on the region’s relationships with China and other non-Western Hemisphere actors, as well as transnational organized crime and populism in the region.

Dr. Evan Ellis is a research professor of Latin American Studies at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, with a focus on the region’s relationships with China and other non-Western Hemisphere actors, as well as transnational organized crime and populism in the region.

This includes some with authoritarian tendencies who seek to deliberately hijack democratic institutions for malevolent ends.

This includes some with authoritarian tendencies who seek to deliberately hijack democratic institutions for malevolent ends. In addition, AMLO has pursued economic policies that would marginalize Mexico’s deeply rooted private sector,

In addition, AMLO has pursued economic policies that would marginalize Mexico’s deeply rooted private sector, It’s worth remembering that Mel Zelaya was accused of receiving illicit funding from Hugo Chavez in Venezuela back in 2010.

It’s worth remembering that Mel Zelaya was accused of receiving illicit funding from Hugo Chavez in Venezuela back in 2010. The present deepening of that crisis of governance theoretically opens a range of options from widespread political violence to a looming impeachment trial in the National Congress, which could result in an even more radical leftist authoritarian leader rising to power in Peru.

The present deepening of that crisis of governance theoretically opens a range of options from widespread political violence to a looming impeachment trial in the National Congress, which could result in an even more radical leftist authoritarian leader rising to power in Peru. Moreover, attempts by some within Peronism in 2020 to replace judges investigating corruption cases involving their networks raised questions about Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the left in Argentina’s aims to consolidate power and undermine the independence of government institutions.

Moreover, attempts by some within Peronism in 2020 to replace judges investigating corruption cases involving their networks raised questions about Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the left in Argentina’s aims to consolidate power and undermine the independence of government institutions.

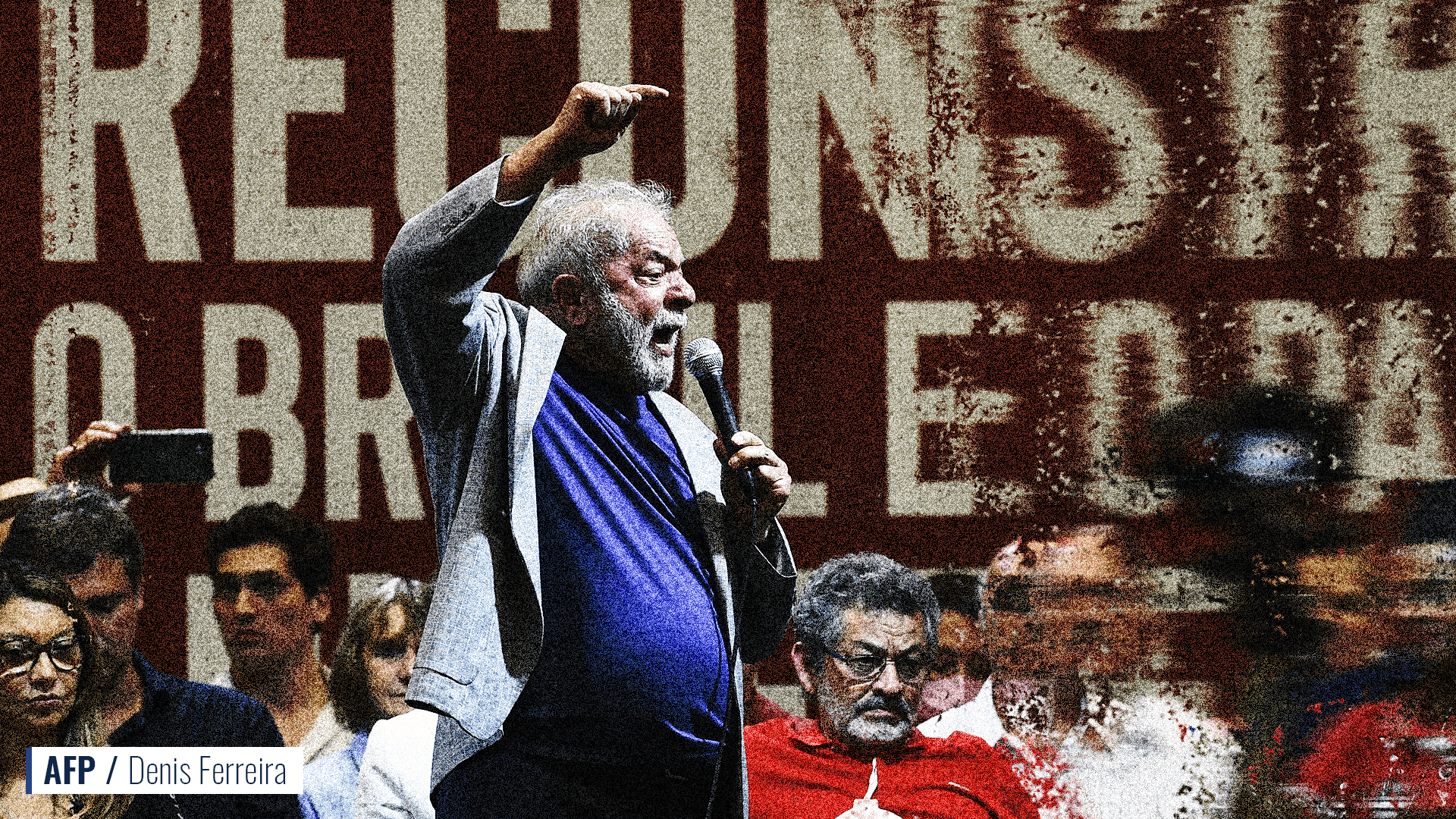

Indeed, Lula’s public statements about prioritizing the need to reduce poverty over fiscal responsibility already suggest Lula’s public intention to depart from his prior pragmatism.

Indeed, Lula’s public statements about prioritizing the need to reduce poverty over fiscal responsibility already suggest Lula’s public intention to depart from his prior pragmatism.