EXPERT

Issues

Locations

DOWNLOAD

In less than a year, a novel coronavirus originating in China has changed the world as we know it. Like a biological thriller, the virus has led to an ongoing global economic recession, with industry shutdowns, and government mandates to the likes of which have not been seen before. As populations across the globe battled between their individual freedoms and communal safety, world economies and health infrastructures were falling. At the end of September, six months into a pandemic, there were over 33 million confirmed cases and almost one million COVID-19 related deaths. While no region (except Antarctica) was spared, some were hit harder than others.

The novel coronavirus first appeared officially in Latin America on February 26, in Brazil. A region already precariously situated economically and politically, the virus aggravated many of Latin America’s endemic problems and plunged it into a health and economic crisis. Since the first recorded case, Latin America has erupted to become a global epicenter of the virus, with more than 8 million confirmed cases and around 300,000 deaths— approximately 34% of worldwide COVID-19 related deaths in a region with only 9% of the world’s population (for more read our COVID-19 Tracker).

SFS COVID-19 Latin America Tracker

For many regional experts, this is not a surprise. Latin America has large informal economies, inadequate sanitation, fragmented health systems, overpopulated cities, and was starting its winter season when the pandemic struck. Of all the regions of the world that have been heavily infected, it stood perhaps the worst chance of containing the virus.

In early April, Latin America still trailed Europe and the United States, with experts suggesting the peak of coronavirus contagion in the region would happen toward the beginning of June. In June, week after week, Latin America seemed to be “amidst its peak,” until the end of the month, when the World Health Organization declared the region the new epicenter of the virus (for more detail on how Latin American lockdowns evolved over time see our heat maps in the link below). By the time Latin America came into the limelight, however, a global narrative had already been formed filled with misconceptions about the virus and disinformation about its origins.

Latin America Lockdowns for COVID-19

The following Situation Report (SITREP) provides research, writings, and short videos, from researchers and international fellows of the Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS), analyzing the geopolitical,

economic, and security effects of the novel coronavirus. Since the start of the pandemic, SFS has been carefully studying the spread of COVID-19 in Latin America and analyzing the various effects it has on the region, relevant for U.S. national security. This SITREP provides our analysis through a combination of videos, info-graphics, and specific case studies that highlight important patterns and trends in Latin America stemming from the coronavirus pandemic and its relevance for U.S. foreign policy and national security.

Correcting Misconceptions

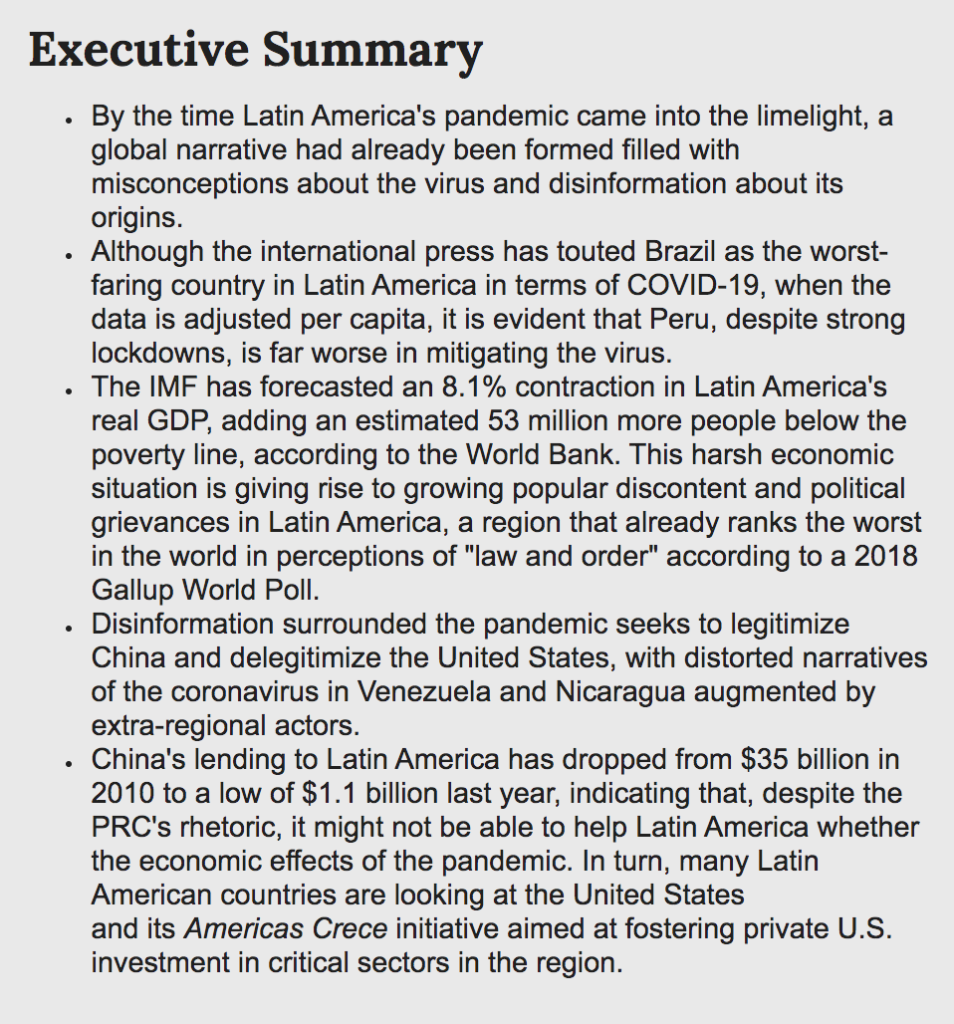

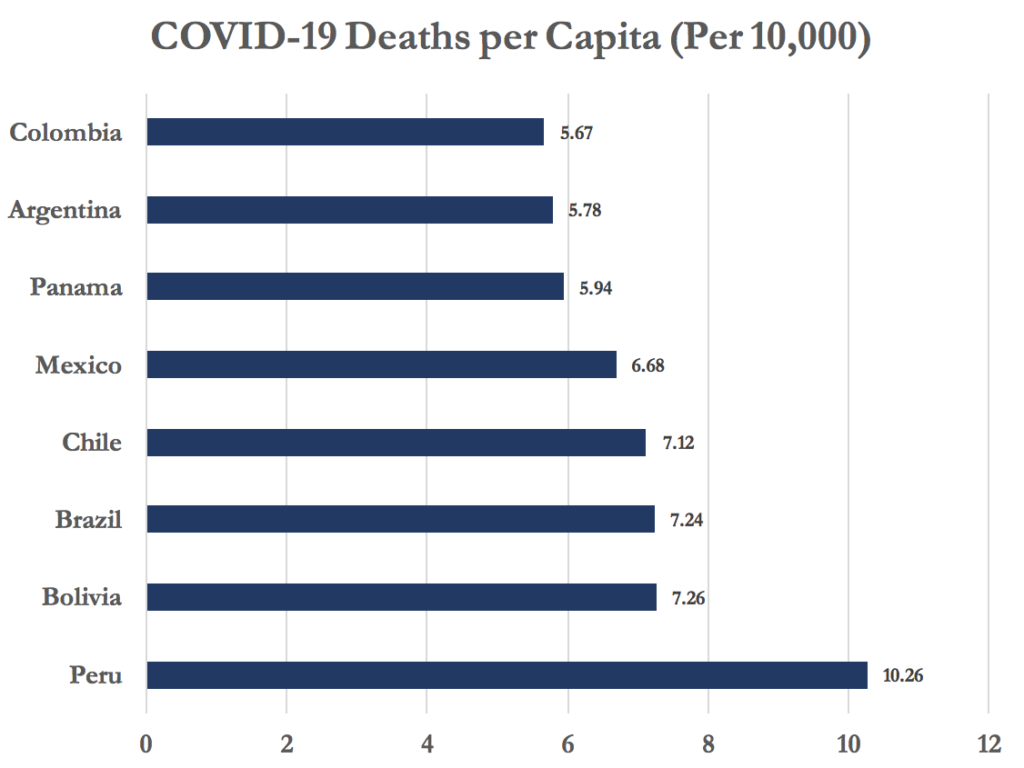

Although almost no countries handled the health crisis without criticism, few were reprimanded more on the world stage than Brazil. President Jair Bolsonaro was discredited by the international community and ridiculed by the press for apparently doing too little to stop the spread of the virus in Brazil. Throughout the pandemic, Brazil appeared to have the worst contagion in the region with the highest gross number of confirmed cases and related deaths. But when adjusting for population size, it was revealed that there were far worse cases than Brazil in Latin America.

Presently, the countries in Latin America with the highest number of COVID-19 related deaths per capita are Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Mexico, and Brazil, each surpassing 6 deaths per 10,000 inhabitants, while most countries, on average, sit at 3.2 deaths per 10,000. According to Johns Hopkins University, Peru’s per capita COVID-19 mortality rate is higher than that of any other nation except a small European country called San Marino with a population of only 34,000.

Peru v. Brazil on the World Stage

Peru has received very little international press compared to Brazil, however, week after week, it consistently topped the list as having the worst community spread and related deaths of the virus in the region. The large informal economy, where more than two-thirds of the population works, and the bustling capital city of Lima (a preferred passage to popular tourist destinations like Macho Pichu in Cusco) made Peru the perfect victim of the novel coronavirus.

Although Brazil was criticized for taking a seemingly laissez-faire approach to the virus, with state governors in charge of implementing mitigation measures, the data shows the viral outbreak was much worse in Peru. President Martín Vizcarra’s government instituted strict, country-wide quarantines in mid-March before Peru hit “day zero” of confirmed cases. On March 15, Peru announced its first national State of Emergency for 15 days, while closing all borders; suspending work, school, and public events; and establishing a mandatory quarantine, prior to the country’s one hundredth confirmed case of COVID-19.

The situation in Peru seemed to deteriorate, even as stricter measures were taken. Many Peruvians were forced to disobey quarantines and other mitigation measures in order to make a living in the informal economy or ensure basic human necessities. For example, according to a 2017 census, less than half the population owned a fridge, making frequent stops to crowded marketplaces nonnegotiable. The overcrowded conditions in Lima, where, according to one economist, more than 30% of households have four or more people sleeping in the same room, certainly did not help when mandatory stay-at-home orders took effect. Mixing sick people with the healthy in a country that, according to one index, ranks among the lowest in the region in terms of healthcare—turned out to be catastrophic. By June, almost 85% of Peru’s ICU beds with ventilators were currently occupied as the country went into a “health catastrophe” (for more watch a short video by our SFS International Fellow).

COVID-19 in Peru by Dardo López-Dolz

Brazil, on the other hand, handled the pandemic differently. Like Peru, the larger South American country did experience a heavy contagion of COVID-19 that has infected at least 5 million people, including President Bolsonaro, but the health system survived. While the press focused on President Bolsonaro’s routine clash with his governors and health experts on how to handle the virus, Brazil’s federal system ensured that at least parts of the country had strong mitigation measures. Of the 27 states, more than a third had quarantine measures in place for most of the pandemic, thus, it’s not accurate to say that Brazil did nothing to contain the virus.

It is clear, however, that President Bolsonaro preferred to keep Latin America’s largest economy alive by opting against stronger mitigation measures that would hurt the country’s workforce. This has paid off as Brazil, in June, recorded its best trade balance since records started in 1989 and the Ibovespa, the Brazilian stock exchange, accumulated an increase of around 50 percent, which is the best second quarter since 1997. As a result, contrary to most world leaders, President Bolsonaro’s popularity has risen during the pandemic, hitting his highest approval ratings in his 20 months in office (for more watch a short video by our SFS International Fellow).

COVID-19 in Brazil by Leonardo Coutinho

Heading Towards Hard Times

Before the pandemic, the decline in the price of commodities and rising insecurity had already placed several countries in Latin America on the path to a recession. Earlier this year, prior to the pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had projected the region’s growth at 1.6% with recession setting in several countries. This projection was updated recently to account for economic shocks caused by the pandemic, and the IMF now forecasts an 8.1% contraction in the region as a whole.

This makes Latin America the hardest hit region in the world, economically, by the virus. COVID-19 is causing the region’s worst economic crisis since the “lost decade” of the 1980s where foreign debt exceeded the earning power for many countries, resulting in Latin America experiencing negative growth for more than a half-decade.

To brace for this, a majority of countries in the region began implanting fiscal policy responses in mid-March to curb the economic effects of the coronavirus and revive their countries’ hardest-hit sectors. A difficult undertaking for a region with low economic freedom, most countries tried to stimulate the economies by offering small business loans. While other countries, instead, offered stimulus packages to individuals, failing to curb the most severe economic impacts (for more read a fact sheet by our SFS Graduate Fellow).

SFS Fact Sheet on COVID-19 in Latin America by Allison Reichel

Currently, Latin America’s hardest-hit sectors are tourism and informal markets. As the region and world experience both labor and productivity shocks, the next steps toward recovery are crucial. Rebounding from such stark supply shocks is likely to take years meanwhile shifts in demand are also evident. In the United States, recent trends have shown that states that re-open are not experiencing much larger increases in travel and leisure. This has implications on the demand side as well; while the travel industry is, once again, able to supply goods and services at a limited capacity, it appears that individual demand is still deferred and may continue to stagnate even after the immediate threats from the pandemic subside.

Costa Rica, falling tourism and rising unemployment

In Costa Rica, the economy is hugely dependent on tourism accounting for 8.2% of the nation’s GDP and the employment of 220,000 people. As a result, Costa Rica announced a $1.5 billion economic package targeted at small to medium-sized businesses, to be used for liquidity or re-opening costs, both major struggles of small businesses that typically do not have large liquid assets.

Tourism isn’t the only sector in decline in the country. As the economy contracts, the impact is most heavily felt in commerce, transport, hotel and restaurant, and construction sectors, shown through rising unemployment numbers. In the second quarter, Costa Rica’s unemployment reached 24%, translating into some 550,000 people out of work, the highest on record since 1991.

Costa Rica’s unemployment levels gave way to an economic depression that prompted President Alvarado to propose a national dialogue to resolve the increasing debt and unemployment in the country. The dialogue was canceled on Thursday, October 15, just days before it was set to start, due to lack of participation. The Costa Rican Union of Chambers and Associations of the Private Business Sector (UCCAEP) and the National Agricultural Alliance declined, while many other economic groups and sectors failed to respond.

Beyond Costa Rica, the overall decline in economic growth and rise in unemployment is expected to exacerbate poverty throughout the region, where, according to the World Bank, an additional 53 million people (to 240 million people total) will cross below the regional poverty line in Latin America. These harsh economic forecasts have Latin American governments concerned, understanding that whenever unemployment surpasses 10% for any extended period of time, social and political unrest is soon to follow.

The Coming Instability

Much like the economies in Latin America, the region sits at a particularly disadvantaged situation in terms of security. Latin America is known as one of the most insecure regions in the world. For the ninth year running, Latin Americans scored lowest on Gallup’s 2018 Law and Order report, specifically feeling “least likely among all global regions to feel secure in their communities,” underscoring the depth of the problem and how it is felt among its citizens. The deteriorating economic situation in many countries presents a governance challenge as social unrest and insecurity are on the rise.

Bolivia, Colombia, and Chile haven’t been the worst cases in terms of the health pandemic, but prior to the coronavirus outbreak, all countries had been battling a political pandemic. Internal chaos and massive protests were flared by tax increases, small hikes in subway fares, and upcoming elections. In the fall of 2019, Bolivia, Colombia, and Chile all exhibited internal instability and mass national protests. As the pandemic added another layer to the instability, worsening conditions in Colombia, Chile, and Bolivia were made more vulnerable by manipulation from external actors.

Bolivia back in the abyss

Although Bolivia was not the hardest hit in the region in terms of the spread of the coronavirus, they have been battling a political pandemic since last year. Still in a state of chaos from a sham election in 2019 that forced former President Evo Morales to flee the country, the long road back to democracy for Bolivia was complicated by the global pandemic that began in 2020. When the pandemic struck Bolivia, new elections hung in the balance and acted as a steady source of conflict for the interim government of President Jeanine Añez.

In May, in the midst of the pandemic, Evo Morales, even while exiled in Argentina, stoked the tension when he proclaimed elections had to be held in 90 days, followed by a legislative proposal by his Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) political party that controls two-thirds of the Bolivian Congress. This put President Añez in a precarious position- balancing the pressure to hold elections in Bolivia at a time when the country was still dealing with the coronavirus. This intensified in August when reports stated Evo Morales-affiliated local proxies in Bolivia orchestrated protests and roadblocks to impede the delivery of oxygen to hospitals, in what was deemed by the Bolivian government as crimes against humanity. It was reported that armed groups were attempting to generate chaos and attack the country’s fragile democracy.

Despite the best efforts by the Bolivian people to rid themselves of Evo Morales and his regime, the virus turned out to be more than a health crisis for Bolivia and was used to fracture the political unity that had proven successful the year prior. With a fragmented opposition, the MAS political party won the recent election on October 18 and Evo Morales’ former finance minister, Luis Arce, is now the president-elect of Bolivia, which is heading toward increased internal conflict.

In a seemingly coordinated attack on Latin America, Colombia and Chile are also facing increasing internal divisions as they fell prey to the same external forces exacerbating various grievances within each country.

Dual protests in Colombia & Chile

On September 9th, a Colombian cabdriver, Javier Ordoñez, was killed by police in Bogota, in a case that was eerily similar to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. National protests immediately erupted throughout Colombia with calls to “defund the police,” while the hashtag #ColombianLivesMatter went viral on social media. Like the George Floyd protests, what started peacefully quickly exploded into violence where 56 police stations were attacked resulting in the death of at least 9 protestors in Bogota and Cali.

While at first glance the U.S. and Colombia protests may seem unrelated to COVID-19, the staggering economic impact of the virus has exacerbated conditions in many countries where social crisis and political instability is on the rise. For Colombia, this is especially worrisome since its belligerent neighbor, the regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, stands at the ready to exploit any opportunity to weaken one of its harshest critics, the Colombian government.

The Maduro regime has already shown it’s capable of using mass protests as an asymmetric weapon of choice throughout Latin America. Last November, protests rocked Colombia over possible austerity measures, like pension and tax reforms. More than 200,000 protestors came out in enough force to close borders and deploy national troops. And while some may have had legitimate grievances, many were stoked by external forces from Cuba and Venezuela.

Chile also faced massive protests prior to Colombia. In October 2019, mass demonstrations against an incremental increase in metro fares resulted in violent protests that burned the metro system in Santiago and attacked police and military installations. Chilean President Sebastian Piñera, who admitted he was caught unaware of the size and intensity of the violence, also, pointed to “foreign forces” behind the protests much like what happened in Colombia a month later.

A study that analyzed 7.6 million digital interactions (including posts on YouTube, Facebook, public Telegram or WhatsApp groups, or digital news media) on unrest in Colombia and Chile found that less than 1 percent of users generated more than 28 percent of the social media content in both countries; and 58 percent of those accounts shared their geolocation originated in Venezuela and Cuba. These cyber-enabled networks on social media would prove useful during the pandemic, driving disinformation and heightening fears about the novel coronavirus.

The force of Chile’s protests last year manifested in a public referendum that took place this year on October 25. President Piñera agreed to the plebiscite after a month of protests in the country. Millions of Chileans came out to overwhelmingly vote to change their Constitution. The public also voted on who is going to change the Constitution- a body of 155 citizens to be voted on April 11, 2021.

As protests surged, Latin American governments found themselves in a position to adapt as quarantines grew longer. The rapidly changing situation and lack of complete information, however, bested even the most well-intentioned leaders. But some seemingly used the pandemic to institute heavy-handed responses, raising red flags about the autocratic nature of these governments and subsequent human rights violations.

Autocracy or Safety in El Salvador and Argentina?

El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele was one of the most proactive in the region in addressing the virus, closing borders and shutting down flights, even before his country saw its first recorded case. Bukele then strictly enforced quarantine, sending violators to “containment centers” where individuals reported being held in detention with poor conditions and with those who tested positive for COVID-19, worsening the community spread in the prisons. This practice had been denounced by the Supreme Court three separate times, with the most recent on April 15, 2020. Bukele dismissed them all, even calling for tougher responses by the police and military to stop Salvadorans from breaking quarantine, which was seen a week later when he used the army to cordon off an entire town accused of being in noncompliance. Bukele continued to battle the Supreme Court on May 30 when the National Assembly proposed a bill to immediately lift quarantine though Bukele wanted to wait. He has vetoed the bill twice, as the Central American country struggles under the economic strain of prolonged lockdowns.

Further south, Alberto Fernández’s Argentina is coming under fire for using the coronavirus crisis as a way to introduce authoritarian measures. Just over two weeks after the administration implemented Decree No. 297/2020, which called for a mandatory lockdown and social isolation of the population, Amnesty International Argentina issued an alert over excessive violence in the police force during the mandatory quarantine. This alert was supplemented by an open letter issued by the think tank Fundación Internacional para la Libertad that expressed concern over the way President Fernández has responded to the coronavirus pandemic. Signed by former President Mauricio Macri and former Security Minister Patricia Bullrich, among others, the letter states “instead of some understandable restrictions of freedom, several countries are imposing confinement with minimal exceptions, the impossibility of working and producing and the manipulation of information.”

Combatting Disinformation

Although Latin American countries experienced varied fallouts from the virus, disinformation blanketed the region in a coordinated attempt by China and its regional allies to convince the world that the United States was secretly the original source of COVID-19. In March, a spokesperson for the Chinese government said the U.S. Army might have brought the virus to Wuhan, fueling conspiracy theories and the propaganda machine in Latin America. This blatant propaganda was echoed by certain autocratic leaders in the region, such as Bolivia’s exiled former president, Evo Morales, who repeated the false claim by China and also stated that “China [has already] won the third world war.”

Fake News in Bolivia

Although all of Latin America was hard-hit by propaganda, Bolivia sits at a particularly disadvantaged position, as former President Evo Morales continued to drive things behind the scenes and move his base from allied countries across the region. So forceful was the propaganda from Morales and his allies that Bolivia’s Ministry of Defense released the infographic, “Disinformation during the coronavirus pandemic,” reminding the population to be careful of where they get their information.

All of this fake news and propaganda worked to destabilize a transitioning democracy already fragile because of the political circumstances. The threat of a violent protest due to propaganda was so great in Bolivia that President Jeanine Añéz enacted Supreme Court Decree No. 4200, where Article 13-2 criminalizes disinformation, specifically any person to “misinform or cause uncertainty to the population will be subject to criminal charges for crimes against public health.”

The COVID-19 disinformation campaign was accompanied by medical diplomacy from Cuba and China and an apparent Sino-Cuban “wonder drug,” which was supposed to be the cure for the coronavirus. As Latin America continues to wage war against this biological agent, China, Cuba, Venezuela, and other regional allies, are waging another type of war laced with lies, half-truths, and aggressive propaganda to delegitimize the United States in Latin America.

The propaganda effort is focused on attacking U.S. allies in Latin America, such as Brazil, Bolivia, and Colombia, exacerbating public sentiments against its political leaders, while distracting from other potential coronavirus hotspots in the region who simply refused to accurately report its data. Nicaragua and Venezuela were among the most notable who had erratic reporting from the start of the pandemic.

False Reporting in Nicaragua

Nicaragua’s reporting of the virus was erratic from the start, with their confirmed cases jumping back and forth, contrary to most countries in Latin America. The irregular reporting was first noticeable on the Ministry of Health’s Facebook page, where the same COVID-19 update video was played for weeks. To the world’s alarm, when the mismanagement of the virus was reported, the Daniel Ortega government continued its denial and secrecy. On May 18, 700 doctors from public and private practices signed a petition urging Ortega to acknowledge the danger of the coronavirus. Almost a month later, many of those doctors were fired in an apparent retaliation by the Ortega regime. This compromised data was coupled with complete inaction on the government’s part to protect its citizens in Nicaragua.

Moreover, throughout the pandemic, Nicaragua has been notably absent from taking any mitigation measures, despite the virus’ wide reach to every Central American country. Contrary to advice from health professionals, in early April, Nicaragua opted to hold a massive public rally of “love in the time of COVID-19,” while the rest of the world delved into preventive measures to slow the spread of the virus. After this infamous parade and a month of the government encouraging citizens to go about their normal daily routines, the government still stressed that the novel coronavirus had not affected its country maintaining that it only had five (5) confirmed COVID-19 related deaths and an abnormal 31 percent Case Fatality Rate.

The Case Fatality Rate (CFR) outliers, or those with a larger rate than average, in the early months of tracking were Belize, Suriname, and Nicaragua. Nicaragua suspiciously left that list after jumping from 25 confirmed cases to 294 cases on May 19, a day after the public petition from Nicaraguan doctors. With only 17 confirmed COVID-19 related deaths at that time, the sudden spike of contagion in Nicaragua dropped their CFR to 2.24 percent after having a 15 – 20 percent death rate for most of the pandemic. International outrage may have led Nicaragua to normalize their coronavirus data, but it’s apparent the government still isn’t reporting credible numbers. This lack of transparency has an independent group, Observatorio Cuidadano, reporting thousands more confirmed cases and deaths in the country than the official count in Nicaragua (for more watch a short video by Nicaraguan civil society leader).

COVID-19 in Nicaragua by Felix Maradiaga

Maduro’s Virus Victimization in Venezuela

As Nicaragua was endangering its citizens with inaction during the coronavirus, its ideological ally, the Maduro regime in Venezuela, capitalized on COVID-19 to enhance its social control and repression of the Venezuelan people.

The coronavirus was used as a tool to increase fear in Venezuelans by controlling healthcare and food distribution, enhancing social control. These elements are used as part of the regime’s repressive apparatus and easily manipulated by external actors in a disinformation campaign that seeks to delegitimize the United States. Contrary to Nicaragua, Venezuela took strict quarantine measures, using Cuban and other community doctors from the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM in Spanish) based in Caracas to gather intelligence and identify dissidents to the Maduro regime.

Internationally, the Maduro regime plays the victim card to the international community and blames the United States for the economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, as Venezuela partners with Russia and China for establishing a “medical bridge,” mostly through cargo flights of coronavirus aid through Africa.

The “victimhood” narrative was complemented by a robust propaganda effort to distract the Venezuelan population and the world. In a national address in late February, as the virus was just beginning to spread in the United States, Maduro said there was “much global analysis that shows that the coronavirus could be a strain [originating in the U.S.] created for biological warfare against China.” Maduro followed this up by calling for an investigation to determine whether the virus was a biological weapon. The regime’s regional echo-chamber of state media from allied countries, such as Cuba and Nicaragua, and associated social media began repeating the same false claim (for more watch a short video by our SFS Senior Fellow).

COVID-19 in Venezuela by Jose Gustavo Arocha

A Challenge, And An Opportunity

While the entire region continues to sit at a vulnerable state, the political influence of external state actors, namely China, is on the rise in Latin America. The last time the world faced a grim economic forecast was after the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. Fortunately for Latin America, this crisis came right before a boom in commodity prices that helped many of the export-oriented countries in the region weather the economic effects. Trade and investment from China, in particular, was key, as the PRC nearly double its demand for Latin America’s raw materials in the three years after the global financial crisis.

In 2020, times have changed. China itself is weathering an economic downturn and is also facing reputational harm from its negligence during the pandemic. Its lending to Latin America has been in decline for several years, dropping from a high of more than $35 billion in 2010 to a low of $1.1 billion in Chinese finance to the region’s governments last year. Understanding that China may not be the “white knight” sparing the region from the worst effects of the pandemic, many Latin American countries are looking at the United States.

The United States América Crece Program, also known as the Growth in the Americas initiative, brought to life in 2018, seeks to foster Latin American regional growth through U.S. private investment in infrastructure, energy, and other critical sectors. This initiative seeks to work closely with governments across the region to strengthen crucial aspects of governance and foster growth in areas such as energy, airports, telecommunications, etc. Acting as a link between the U.S. private sector and opportunities in the region, the initiative’s main goal is to connect Latin America to both private investors and government resources in the United States. Expanding this program would allow for the creation of jobs, capital inflow, and additional infrastructure to aid the region in repairing damage caused by the economic effects of COVID-19.

A recent election for the head of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the region’s largest source of development financing, placed, for the first time in the institution’s 60-year history, an American at its helm. Mauricio Claver-Carone, who previously served as the White House point-man for the Western Hemisphere, overcame a campaign to postpone the September election and earned votes from 30 of the IDB’s 48 governors, in a clear message that Latin America is looking toward U.S. leadership.

In a recent virtual conference hosted by the American Enterprise Institute, Claver-Carone mentioned that small-to-medium size businesses are the motors for economic growth in the Americas and he looks to break the bottleneck of investments to this sector. In a separate interview, he clearly addressed the future vision of the IDB vis-à-vis China, stating that “China plays an important role in international trade, but it is a country far from the Americas and completely controlled by a state. So, what we [Claver-Carone] are looking for is to fulfill the dream of Pan-Americanism, which has existed since before China was an economic power.”

Ironically, the pandemic, with all the challenges it’s mounted in Latin America, has presented another opportunity for the region to come out of a crisis better than before. To do so, regional governments must take a hard look at its foreign policy with China and revisit the root causes of why the rule of law remains weak throughout the region. If successful, there is no reason why the disastrous effects of COVID-19 should lead to another “lost decade” for Latin America.

SFS Team

SFS Team