Chinese spy balloons were spotted in the skies of the Caribbean, while Iranian warships sailed into the South Atlantic. Incidents that may seem isolated are correlated with several conflicts taking place in Central and South America as Great Power Competition turns into Great Power Confrontation, coming to the shores of the Western Hemisphere.

Three years into a China-induced global pandemic, one year into the Ukraine war, Russia pulling out of the nuclear START treaty, and Iran’s Fordow nuclear site recently discovered to have close to weapons grade uranium particles—the world is inching closer to a global conflict that could see direct and non-direct actions escalate in various theaters simultaneously.

The VRIC alliance, more evident than ever, has diminished its geographic disadvantage with the United States by building joint capabilities and strategically positioning itself in Latin America and the Caribbean. Beyond all the natural differences each external state actor has with one another lies a mutually beneficial coordinated effort to shape a supposedly “multipolar” world, redesigning the international order in an authoritarian image and likeness. The primary target is the United States and democracies worldwide.

Appearing to act autonomously, Russia, Iran, and China’s actions in Latin America are becoming increasingly coordinated and more dangerous. By occupying neglected geopolitical spaces, the VRIC is capitalizing on Latin America’s turn towards the radical Left. Last year’s elections in Brazil and Colombia solidified the VRIC’s strategic gains in South America, presenting new opportunities to further destabilize the region and undermine confidence in democracy and freedom.

In 1832, the Prussian military strategist, Carl von Clausewitz wrote, “War is the realm of uncertainty; three-quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.”

The world is charting into uncertain waters. Since 2019, the VRIC Monitor has sought to help see through this fog and in the current issue, Number 29, we take a holistic look at this year’s major geopolitical developments in Latin America and the Caribbean that are of interest to U.S. national security.

IRANIAN WARSHIPS BERTHED IN BRAZIL

I.R.I.S. DENA DOCKED AT PORTOSRIO IN RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL ON FEBRUARY 28, 2023 | CREDIT: SAMUEL FILHO / RÁDIO 93FM

On January 11, Rear Admiral Shahram Irani stated that Iran’s Navy has deployed to all the strategic straits in the world except two, one of which is the Panama Canal. This prompted the Panama Canal Authority to release a communique signaling its neutrality commitments to keep the canal open to all vessels, during war and peace, as long as they comply with international and interoceanic norms and dues.

In mid-January, after the inauguration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil granted permission for two Iranian warships, the I.R.I.S. Makran and the I.R.I.S. Dena, to berth at a port in Rio de Janeiro between January 23 and 30. The first naval ship, the Makran, is a former crude oil tanker refitted as an expeditionary seabase. It is the largest ship in Iran’s Navy. It was part of an initial voyage into the South Atlantic in 2021 prior to sailing north into the Baltic Sea en route to St. Petersburg, Russia. The second ship, the Dena, is a Moudge class frigate equipped with advanced weapons systems such as anti-ship missiles, naval cannons, and torpedo launchers. Both vessels are part of the 86th Naval Fleet of the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN) that has been used for various maritime operations to include providing security for naval exercises and asymmetric amphibious assaults.

The Iranian warships never arrived in Brazil in January but were spotted passing near Chilean coastal waters before entering the Drake Passage, connecting the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean to the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean near Antarctica. It’s reported that Chile denied the Iranian naval flotilla access to its territorial waters, but the request did not go to the defense or foreign ministry but rather directly to La Moneda, which houses the president’s office and general secretariat of Chile. The Drake Passage is also the only interoceanic channel in the Western Hemisphere not passing through sovereign territorial waters.

Iran ran into more obstacles as it entered the South Atlantic. The flotilla remained on “stand-by” as it approached Argentina’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), a convenient hiding place for the Iranian warships who apparently had to delay its arrival to Brazil.

Argentina’s extended EEZ, north of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) and east of Argentina, at nautical mile 201, is the epicenter of China’s illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing fleet known as Chinese squid jiggers. China’s Maritime Militia, an auxiliary force of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), is known to “go dark” in the South China Sea by camouflaging itself through fishing boats that surround maritime borders. The Iranian warships sailing in the South Atlantic went dark in early February as it was approaching Argentina’s EEZ and nautical mile 201 only to reappear near Uruguay’s territorial waters days later.

According to data collected by maritime organizations that monitor IUU fishing, at least 433 Chinese vessels have been identified near Argentina’s nautical mile 201 and almost 700,000 hours of clandestine activity has been reported in Argentina’s extended EEZ by a “patch” of Chinese fishing vessels since January 2018. This provides the perfect cover for Iranian warships to conceal any illicit activity prior to entering Brazilian territorial waters.

Another possible reason the Iranian warships were delayed in their voyage to Rio de Janeiro is U.S. countermeasures. One week before the initial scheduled January arrival of the Iranian flotilla to Brazil, the U.S. Air Force dispatched the WC-135R Constant Phoenix ‘nuke sniffer’ jet to measure a baseline of atmospheric radiation and detect unusual spikes. This is the first time the U.S. has conducted an air-sampling sortie mission over the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America, precisely the route that the Iranian warships are to travel.

I.R.I.S. Dena Docked at Portosrio in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil on February 28, 2023 | CREDIT: Samuel Filho / Rádio 93FM

The Iranian warships eventually arrived in Brazil on Sunday, February 26 at approximately 9:00 AM after receiving a reauthorization from the Brazilian Navy to dock in Rio de Janeiro between February 26 and March 4. As the Dena is parked at Portos Rio, the Makran remains afloat near the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema. Meanwhile, Iran and Brazil celebrate 120 years of diplomatic relations by inviting Brazilian diplomats and military officers aboard the I.R.I.S. Dena as it is docked in Rio de Janeiro.

AUTHORITARIAN LEARNING: NORTH AFRICA TO LATIN AMERICA

Nicaragua President Daniel Ortega and Iran's Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian in Managua, Nicaragua on February 2, 2023 | CREDIT: Canal 6 / AFP

Iran’s naval deployment to South America coincided with a high-level diplomatic visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian to Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Cuba in early February. On February 2, Minister Abdollahian touched down in Managua and was welcomed by his Nicaraguan counterpart Foreign Minister Denis Moncada and the sons of dictator Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. It appears that Managua and Tehran will begin a series of binational investments to replicate the commercial-military model Iran installed in Venezuela, turning Nicaragua into the hub to export Iranian products throughout Central America. A point emphasized by Laureano Ortega Murillo, a son of Daniel Ortega and his senior advisor for foreign trade and investment.

One week after Iran’s visit to Nicaragua, on February 9, Daniel Ortega announced the release of 222 political prisoners who were subsequently deported to the United States. 94 of them were stripped of their Nicaraguan citizenship. This happened on the same day that the Iranian regime released seven female activists from Tehran’s Evin prison after the Supreme Leader granted amnesty to several political prisoners that were incarcerated during the 2022 protest of the regime’s morality police.

After Managua, Iranian Foreign Minister Abdollahian visited Caracas to follow up on the 20-year strategic deal signed with Venezuela in 2022 on energy, technology, commerce, agriculture, and defense. The visit followed the delivery of more than one thousand Iranian manufactured cars to Venezuela, located near a strategic military base in Maracay, Aragua State, of Venezuela.

On the same day that Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro met with Iran’s foreign minister, he also signed a major reciprocal commercial agreement with Colombia. President Gustavo Petro of Colombia is warming up to Venezuela, and by extension, to its international allies, such as the Islamic Republic of Iran. On February 24, the Iranian deputy foreign minister traveled to Bogota for bilateral meetings with Colombia’s foreign and agricultural ministry in a continuation of high-level meetings and visits by Iran since President Petro’s inauguration in August 2022.

The Iranian foreign minister’s three country tour of Latin America concluded on February 4 in Havana, to discuss, among other issues, counter-terrorism cooperation with Cuba. This follows a U.S. diplomatic visit in January to Havana to also discuss counter-terrorism cooperation, as well as migration and counter-narcotics issues with the communist regime.

Cuban Foreign Affairs Minister Bruno Rodriguez (R) and Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian (L) shake hands before a meeting at the Revolution Palace in Havana on February 4, 2023 | CREDIT: Yander Zamora / AFP

Prior to Foreign Minister Abdollahian’s visit to Latin America he stopped over in Mauritania in North Africa. After Morocco and Israel normalized relations in 2020, the VRIC has increased its presence in the Islamic Maghreb in support of the Polisario Front in the Western Sahara, which ended its ceasefire with Morocco. Both Russia and Iran have unofficially supported the rebel Sahrawi separatist movement, the Polisario Front, by increasing its presence in neighboring countries Algeria and Mauritania.

The expansion of Iran’s presence in North Africa while intensifying its activities in Latin America is a result of the Islamic Republic’s expansionist foreign policy that relies on building proxy governments in both regions.

The Iranian foreign minister’s visit to Mauritania mirrored a similar visit from Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro to North Africa in June 2022 prior to traveling to the Middle East. According to press reports about Maduro’s trip to Algeria, Venezuela pledged $20 million to support the Polisario Front with military equipment. Much like Venezuela, Algeria is quickly becoming a regional hub to expand the VRIC’s geopolitical influence throughout North Africa, serving as a bridge to a transregional threat network in Latin America and the Caribbean.

CHINA’S SECOND HIGH-ALTITUDE SPY BALLOON

CHINA’S HIGH ALTITUDE SURVEILLANCE BALLON SPOTTED IN VALLEDUPAR, COLOMBIA ON FEBRUARY 3, 2023 | CREDIT: CARLOS PINEDA / TWITTER @CARLOSP47243960

On February 2, as Iran’s foreign minister went wheels down in Nicaragua—a white, spherical unidentified flying object was observed in the skies above Costa Rica. Three days earlier, another High-Altitude Surveillance Balloon from China violated North American airspace through Alaska, passing over Canada, and entering the United States via Montana traveling for four days across the continental United States before being shot down over the Atlantic Ocean by the U.S. Air Force as it was leaving South Carolina.

China’s spy balloon raised several alarms in the U.S., given its trajectory flying over sensitive military infrastructure, to include nuclear missile sites, the air base that houses the B-2 stealth bomber, and Strategic Command (STRATCOM) at Offutt Air Force Base near Omaha, Nebraska, which oversees the country’s nuclear forces. In Latin America, however, no alarm bells rang as a second Chinese spy balloon passed through the sovereign airspace of at least three countries in the region.

Chinese officials admitted to owning the second spy balloon spotted over Latin America when Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said that the balloon was an “unmanned research airship” that was derailed due to weather. Colombia’s air force confirmed that the balloon traveled over northern parts of the country on February 3. But contrary to the U.S. reaction to the spy balloon canceling Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s trip to Beijing, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro tweeted that he will “accelerate my trip to China to look for options [to finance] the Bogota metro,” an infrastructure project being built by APCA Transmimetro, a Chinese consortium.

Much like China’s spy balloon that entered the U.S., the second balloon flying over Latin America flew over sensitive military and security infrastructure, to include the Costa Rican Coast Guard (SNGCR) and Colombia’s Combat Air Command No. 3 (CACOM-3), both responsible for maritime drug interdiction (and other) operations along the sensitive and disputed Colombia-Nicaragua maritime border.

Costa Rica does not have an active military, therefore, depends substantially on its Coast Guard to patrol its territorial waters. Last year, the U.S. donated state of the art equipment such as interceptor boats and secure communications, to complement the two patrol vessels donated in 2017 to engage in joint operations in the Caribbean.

China’s second spy balloon was initially spotted on February 2 in Jaco, a beach town on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica, southwest of the capital city, San José. It was seen leaving the country off the Caribbean coast in the province of Limón. The estimated trajectory of China’s second spy balloon flew near Costa Rican Coast Guard stations that have the mission of protecting the coast from drug trafficking and illegal fishing.

In Colombia, the National Air Defense System detected China’s spy balloon on February 3 as it traveled east along the 11th parallel at an average speed of 28 mph and entered the country through Cartagena de Indias before being spotted near Barranquilla and Valledupar on the Caribbean coast. Among other military installations, the spy balloon passed near the Combat Air Command No. 3 (CACOM-3) located at the MG Alberto Pauwels Rodríguez Air Base adjacent to the Ernesto Cortissoz International Airport on the outskirts of Barranquilla. CACOM-3 is the Colombian Air Command that is responsible for a variety of air and sea security operations within Colombian territorial waters, to include patrolling over the San Andrés Archipelago near the disputed maritime border with Nicaragua.

A portion of the maritime border has long been claimed by both countries, and Nicaragua gained fishing rights over a big portion in a 2012 ruling by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. Colombia responded back then by stating it would no longer recognize the ICJ’s jurisdiction on border disputes and continued patrolling the waters, which are used by cartels to move drugs from South to Central America. Last year, the ICJ ruled that Colombia must “immediately cease” patrolling these waters because they are within Nicaragua’s exclusive economic zone, intensifying the decades-long maritime border dispute.

Raising tensions further, on February 23 the Colombian government slammed Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega’s expulsion of jailed political opposition, calling for international monitoring and a criminal inquiry, according to a statement by the Colombian foreign ministry. Six days earlier, on February 17, the Venezuelan foreign ministry released a communique declaring its sovereignty over the Essequibo region, a 160,000-square-kilometer territory that covers almost three fourths of Guyana, and is in dispute by Venezuela. The dispute intensified in 2015 when an estimated 11 billion barrels of oil reserves were discovered along the maritime border of the two countries.

China’s second spy balloon in the Western Hemisphere was last spotted on February 4 in the Venezuelan city of Maracaibo, and was later seen in Valencia near a strategic military base that houses Russian, Chinese, and Iranian military advisors. The balloon’s trajectory in Venezuela flew near Punto Fijo on the Paraguana Peninsula, which is the command-and-control hub for a large “anti-narcotics” operation by the Venezuelan military called Operation Cacique Manaure that began in September 2022.

The official mission of China’s High Altitude Surveillance Balloons is not confirmed; however, it is easy to ascertain that the two balloons, violating U.S. and Latin American airspace, were on an intelligence mission and not used for meteorological purposes. U.S. authorities discovered that the first balloon, shot down off the coast of South Carolina, had “multiple antennas” in addition to other surveillance equipment used “clearly for intelligence surveillance” and “intelligence collection operations,” according to a spokesperson from the U.S. State Department. It’s safe to assume that the second spy balloon from China, flying over Latin America and the Caribbean, had similar signals and surveillance intelligence capabilities. The difference is the second spy balloon, over Latin America, traveled uninterrupted.

China’s spy balloon, which violated the sovereign airspace of Costa Rica, Colombia, and Venezuela, traveled near important military bases and security installations responsible for maritime surveillance and interdiction operations in the Caribbean. A reverse order of battle could be part of the strategic intelligence collected by China that can use high-altitude surveillance spy balloons as a multi-purpose military mission to measure detection capabilities and response times, identify air and sea defense systems, and, most importantly, prepare the maritime battlespace for future asymmetric conflicts in the Caribbean.

The lynchpin for these sort of covert intelligence missions in Latin America is the Venezuelan Armed Forces, who, despite claiming to seize multi-ton shipments of cocaine through its anti-narcotics operation based out of the Paraguana Peninsula—is credibly accused of itself being involved in high-level narcotics trafficking. When Nicolás Maduro made no mention of China’s spy balloon flying over his country but instead chastised the United States for shooting down the other balloon that violated U.S. airspace—it becomes clear that disinformation and subterfuge are part of an effort by Latin American leftist leaders, such as Gustavo Petro, Lula da Silva, Daniel Ortega, and others, to amplify calls for peace while pushing the region toward an asymmetric war.

WEAPONIZED PEACE

China's President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin | CREDIT: AFP

The global context of VRIC activities in Latin America is the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War that passed its one-year mark on February 24. On the heels of the Munich Security Conference, where President Volodymyr Zelenskyy opened with an urgent call for the free world to send more help to Ukraine—China presented a 12-point plan to end the war in Ukraine. Days prior, on February 10, Brazilian President Lula da Silva sat with President Biden at the White House to discuss, among other issues, the “state of democracy” in Brazil and worldwide, to include the Ukraine War.

US President Joe Biden meets with Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, DC, on February 10, 2023 | CREDIT: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds / AFP

On February 24, the anniversary of the war, Lula launched a negotiated peace proposal for the one-year-old war in Ukraine. The proposal insists on creating a group of countries to mediate the conflict, a “Peace Club” as he called it, that could include China, India, and Indonesia.

As Lula was discussing his “peace plan” with President Biden, Iran’s warships were approaching Rio de Janeiro. Almost four months ago, on November 5, 2022, the same Iranian warships that are in Brazil were docked in Jakarta, Indonesia, and offered as a naval diplomatic mission promoting “peace” in advance of negotiations for an Iran-Indonesia preferential trade agreement. Iran, which last year formally applied to join the BRICS bloc—a more than a decade-old grouping of emerging economies—is joining Beijing in pressuring Jakarta to join the BRICS.

Indonesia is a strategic choke point with around 25 percent of global trade passing through the Strait of Malacca. When the I.R.I.S. Makran and I.R.I.S. Dena ported in Jakarta in 2022, they spoke of “maritime security” and “protection of trade routes.” An Iranian disinformation campaign that came to Latin America in 2023 when its two warships berthed in Brazil. The false narrative is amplified by Iran’s ambassador in Brasilia who welcomed the warships with a tweet on February 26 stating that the “Iranian Navy has at all times been a force of safety and security in our region and beyond … to fulfill its principle mission: #PEACE.”

After China’s spy balloon passed through Latin America and the Caribbean, the Chinese leader Xi Jinping welcomed Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi in mid-February to Beijing for a three-day visit. This was Raisi’s first international trip since protests erupted in Iran last year during his participation in the United Nations General Assembly.

China, Russia, and Iran are the central actors in a triple threat axis that is intent on changing the international order. Venezuela is the primary Latin American proxy for this triple axis; however, Lula in Brazil and Petro in Colombia provide the VRIC with new ways and means to weaponize peace in the region and worldwide.

Lula’s efforts at arbitrating the Ukraine War are coupled with Brazil, as of February 6, being included as a guarantor for the peace talks between the Petro government in Colombia and the transnational criminal organization (TCO), the National Liberation Army (ELN). This has been heavily criticized by the Colombian opposition because it provides impunity to criminals and terrorists, which is being reflected by the growth of another major TCO—the “Clan Del Golfo”—who is now imposing curfews in specific cities in Antioquia with little to no response from the Petro government.

Fundamentally, the VRIC’s war against democracy, freedom, and sovereignty, rests on its ability to build a financial system that can stand up to the U.S. dollar, or at least function on the margins of the dollar-dominated world order. In Brazil, Lula’s government strives for “an adjustment” in the governance of the New Development Bank, the so-called “Bank of the BRICS,” by naming his former successor and former president, Dilma Rousseff, as the new head of the bank. Rousseff has openly called for the “the end of the dollar hegemony” in previous public forums.

STRATEGIC CHOKEPOINTS

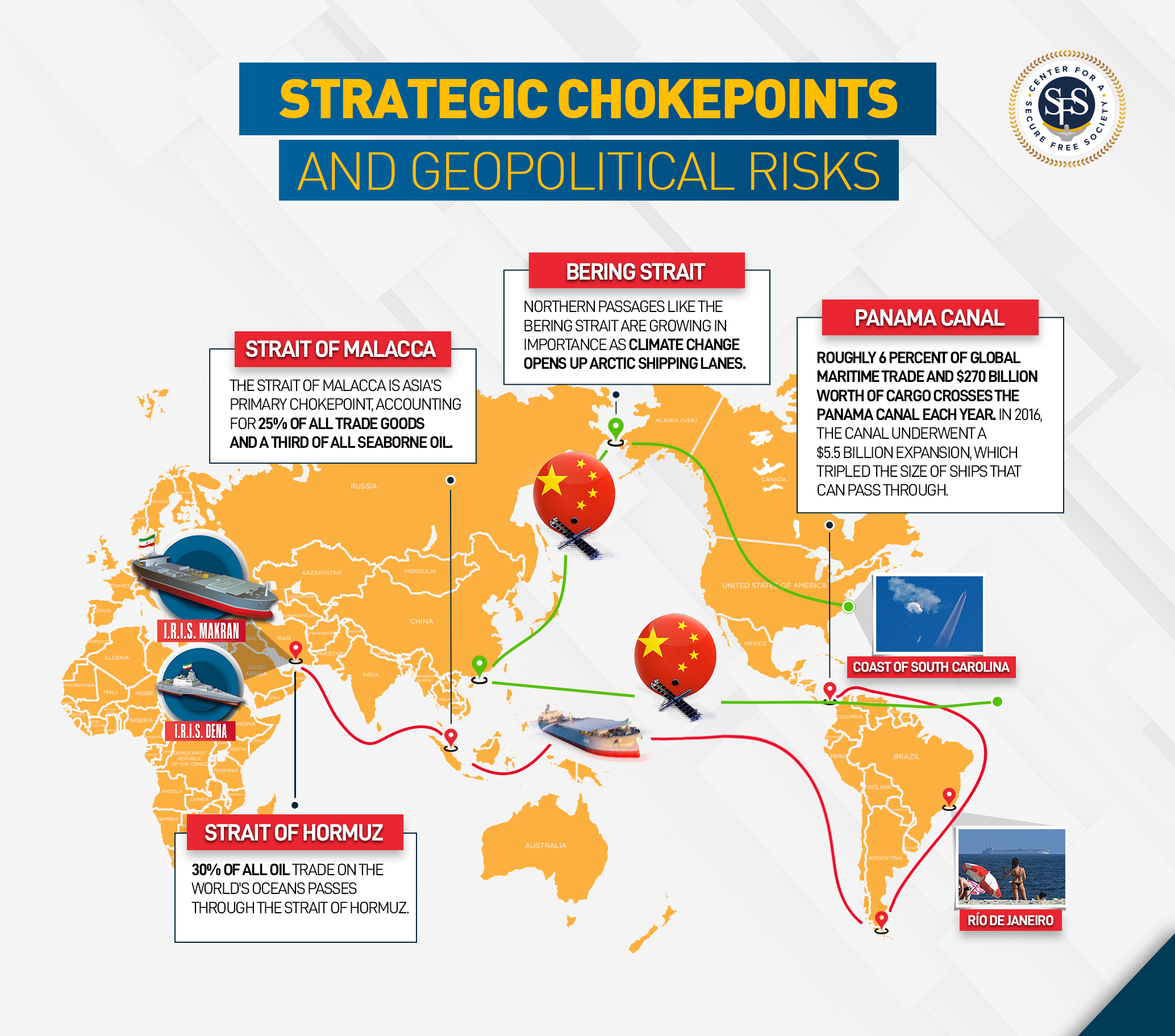

Maritime transport is a key element in international trade. Approximately 80 percent of consumer products are shipped via sea. Making maritime security essential for global commerce. Strategic, narrow passages in the sea are chokepoints that are convenient for trade but also vulnerable to structural and geopolitical risks. When the Iranian Navy states that it will pass, for the first time, through the Panama Canal–this needs to be taken as more than an ambition, it’s a global security risk.

Especially since, for at least part of its blue water voyage, the I.R.I.S. Makran may have been traveling with a Chinese warship. According to maritime bloggers, the Type 052D Yinchuan guided missile destroyer of the PLA’s Navy was detected off the Pacific coast of the United States in early January driving suspicion that it could have been refueled by the Makran after both the Iranian and Chinese warships passed Micronesia and the Polynesian Islands. Iran and China, along with Russia, have held several joint naval exercises in the Gulf of Oman and the Indian Ocean since 2019.

The Panama Canal is the strategic chokepoint for approximately 6 percent of global maritime trade. It has, up to this point, avoided many of the major national security crises that have plagued other strategic chokepoints, such as the Suez Canal or the Straits of Hormuz. This may change if Iran and its “multipolar” allies, the VRIC, are allowed to establish a consistent presence in and around the Panama Canal.

Alfred Thayer Mahan, a U.S. naval historian and strategist, outlined in his 19th century article “Isthmus and Sea Power” that even for those Americans who want to remain isolated in the world, the creation of the [Panama] canal would forcibly end it. “This isolation will pass away, and with it the indifference of foreign nations,” Mahan wrote. These words are proving prophetic as Great Power Competition has arrived on the shores of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Disclaimer: The VRIC Monitor is a monthly report published by the Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS) based on open-source media reporting on Venezuela, Russia, Iran, and China’s activities in Latin America and the Caribbean. The report tracks some of the most relevant articles on credible news sites and social media postings in multiple languages (English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Arabic). Given the inevitably that our tracking picks up government propaganda from state-owned or -controlled media outlets of VRIC nations, these articles are carefully reviewed and do not source more than 20 percent of the overall report. And is intended to report on news that is not reported on by other more credible media and is relevant for understanding VRIC’s influence in Latin America and the Caribbean.

SFS Team

SFS Team